Climate-related risks and

accounting

April 2024

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Contents

1

Executive summary 2

1 Introduction 5

2 Conceptual and methodological considerations 10

2.1 The boundaries of financial reporting 10

2.2 Climate-related risks, accounting and financial stability 12

3 Main issues identified 17

3.1 The extent to which market prices incorporate climate-related risks 17

3.2 The valuation of non-financial assets and liabilities 20

3.3 The incorporation of climate factors into models 24

Box 1 ECB observations on climate change in expected credit losses 24

3.4 Disclosures 27

4 Conclusions and policy discussion 29

References 33

Annex 1: Work on climate-related risks by ESMA in its role as coordinator of accounting

enforcers 36

European Common Enforcement Priorities 36

ECEP assessment 37

Report titled “The heat is on: disclosures of climate-related matters in the financial

statements” 39

Next steps 39

Annex 2: ESRS E1 Climate change 41

Annex 3: IFRS accounting standards and the main issues identified 45

Imprint and acknowlegements 46

Contents

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Executive summary

2

This report analyses how climate-related risks are addressed in International Financial Reporting

Standards (IFRS) and reflected in financial statements prepared in accordance with those

standards, all from a financial stability perspective. It considers ongoing work by the IFRS

Foundation, the European Commission and the European Securities and Markets Authority

(ESMA). The report does not, however, discuss sustainability standards (e.g., the European

Sustainability Reporting Standards or those issued by the International Sustainability Standards

Board), except where they relate to connectivity.

Climate-related risks can affect accounting, as well as the relevance, reliability and materiality of

the information disclosed in the financial statements. The impacts of climate-related risks should be

included in the financial statements to the extent that the recognition criteria set out in IFRS

accounting standards are met – only in that case will the economic events and transactions

carrying those risks result in an asset, liability, income or expense, gain or loss being reported in

the financial statements. For this reason, financial statements may not always be able to fully

capture the impacts of climate-related risks on a reporting entity’s financial position, results and

risks. In particular, financial statements may not adequately reflect (i) risks that materialise beyond

the time horizon over which the entity expects to derive economic benefits from its assets and cash

outflows to settle its liabilities, and (ii) the future actions that an entity may be compelled to take in

order to mitigate and address climate-related risks and to operate as a going concern. In this

regard, prevailing uncertainty about the future impact and timing of the materialisation of climate-

related risks is an important factor to consider when assessing the extent to which accounting

should reflect such risks.

Although accounting is not primarily meant to foster financial stability, there are at least three

channels of transmission: (i) transparency, (ii) behavioural response of economic agents to

accounting information, and (iii) regulation (as accounting is either the starting point or key

reference point when defining prudential requirements for regulated financial institutions).

Accounting for climate-related risks could affect financial stability through any or all of these three

channels. Moreover, while financial institutions have only limited direct exposure to climate-related

risks, their interactions with the real economy (i.e., through loans, insurance contracts or holdings of

securities) indirectly expose them to climate-related risks. The way in which non-financial

corporations include climate-related risks in their financial information may also raise financial

stability concerns.

With these considerations in mind, the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) has assessed how

climate-related risks are addressed in existing IFRS accounting standards and reflected in financial

statements, identifying four relevant issues for financial stability:

1. The incomplete incorporation of climate-related risks in market prices can cause assets to be

overestimated or liabilities to be underestimated, affecting both financial institutions (mainly

through holdings of financial assets) and non-financial corporations (particularly through

tangible assets measured at fair value, such as investment property). The expectation would

be for market prices to gradually incorporate climate-related factors, as the transition to a low-

Executive summary

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Executive summary

3

carbon economy unfolds and as the uncertainty surrounding the physical impacts of climate

change dissipates. However, a scenario of sudden adjustment cannot be completely ruled out.

For instance, this could occur in the event of a sudden and disorderly transition, or due to non-

linearities and the sudden manifestation of the physical impacts of climate change. In any

case, having climate-related risks reflected in the market price of assets is an issue that goes

beyond the accounting realm and should be addressed by appropriate policy tools.

1

2. The effect of climate-related risks on the initial and subsequent valuation of non-financial

assets and liabilities, including property, plant and equipment, intangibles, goodwill, provisions

and off-balance sheet items (e.g., contingent liabilities). Failing to fully include relevant climate-

related risks in impairment tests for non-financial assets may distort their valuation, affecting

non-financial corporations and, indirectly, the financial sector through their exposures thereto.

As a case in point nowadays, failure to adequately consider climate-related risks when valuing

real estate, which plays an important role as collateral in bank lending, could affect financial

stability in the event of sudden value adjustments. Moreover, non-financial corporations

operating in certain sectors may fail to adequately report climate-related liabilities due to the

prevailing uncertainty about the future financial impacts of these risks, among other factors.

3. The incorporation of climate factors into the models used to estimate expected credit losses

under IFRS 9 Financial Instruments or expected cash flows from insurance contracts according

to IFRS 17 Insurance Contracts. It may be operationally difficult for banks and insurance

corporations to incorporate climate-related risks into their models, as they would need to

frequently collect, review and update reliable and sufficiently granular sustainability data.

Furthermore, in the case of catastrophe risks and insurance corporations, relying excessively

on past data could lead to inaccurate estimates of insurance liabilities.

4. Disclosures. Efforts should be made to enhance disclosure requirements about how climate-

related risks are reflected in the financial statements. Even if IFRS accounting standards

contain implicit requirements to disclose relevant information on climate-related risks, those

requirements may go unnoticed and become ineffective, particularly if driven by a strong

judgemental component. This puts the onus on enforcing appropriate interpretation and

application of IFRS accounting standards. Furthermore, expanding the existing disclosure

requirements without due consideration of the underlying estimates and data sources could

have unintended consequences.

The four issues identified ultimately relate to the existing uncertainty about the materialisation of

climate-related risks. They also show that climate-related risks are viewed differently among

stakeholders and reveal a lack of commonly accepted and sound methodologies for estimating their

financial impact. This increases the risk of delayed recognition of climate-related risks in the

financial statements, which could in turn lead to “information shocks” if sudden changes must be

made to the financial statements as expectations are abruptly reassessed, potentially damaging

financial stability via fire sales, higher cost of capital and suboptimal allocation of resources. Even if

outside the accounting realm, further work should be carried out on methodologies to objectively

1

See, among others, European Central Bank and European Systemic Risk Board (2022 and 2023).

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Executive summary

4

gauge the impact of climate-related risks, in order to ensure comparability and aggregation of the

impacts disclosed by individual institutions.

The ESRB has considered possible actions related to the design and implementation of IFRS

accounting standards that could be beneficial for the timely and accurate incorporation of climate-

related risks into the financial statements.

2

With regards to their design, IFRS accounting standards generally allow an entity to reflect climate-

related risks in the financial statements, within the boundaries of financial reporting. However,

several amendments could prove beneficial for users of such financial information and, indirectly,

for financial stability. These amendments relate to (i) the application of the materiality principle

under IAS 1; (ii) the addition of climate factors to the list of indicators of impairment under IAS 36;

(iii) how IAS 37 should be applied in view of climate-related-risks; and (iv) disclosure requirements,

examples and guidance on how climate-related risks should be incorporated into the estimation of

expected credit losses and the fair value of financial instruments (affecting IFRS 7 and IFRS 13).

Work on the accounting treatment of pollutant-pricing (i.e., carbon-pricing) mechanisms should also

be prioritised.

Turning to the implementation of IFRS accounting standards, regulators, microprudential

supervisors and/or accounting enforcers should consider developing guidance on disclosures by

financial institutions, on how climate-related risks can affect the expected credit loss estimates of

banks, and on how to compute cash flows from insurance contracts directly exposed to climate

factors (including natural catastrophe events and home insurance in areas most affected by

climate). Disclosure would be another area warranting further attention by regulators,

microprudential supervisors and/or accounting enforcers.

Given the boundaries of accounting, sustainability standards are crucial when it comes to disclosing

the long-term financial impacts of climate-related risks. The entry into force of sustainability

standards will not have the intended effects if reporting entities do not properly connect

sustainability information with financial information in their financial statements. Insufficient

connectivity can lead to duplications and divergent disclosures under financial and sustainability

reporting, and, more broadly, deteriorate the quality of the information disclosed to capital markets,

with potential consequences for financial stability. To avoid such an undesirable scenario, further

work in this area by the respective standard-setters would be welcome.

Last but not least, the scope of the assurance work carried out by auditors is crucial in this regard.

Auditors can play an important role, particularly when assessing existing disclosures and

challenging estimates affected by climate-related risks. Furthermore, ensuring that sustainability

reporting (including transition plans) is subject to assurance work as part of statutory audits could

be a valuable tool in addressing the lack of connectivity between accounting and sustainability

standards. Work by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board at the global level

and by the Committee of European Audit Oversight Bodies at the EU level is a first step towards

equipping auditors with a common approach to the assurance of sustainability information.

2

The term “implementation” should not be interpreted in connection with Regulation (EC) No 1606/2002 of the European

Parliament and of the Council of 19 July 2002 on the application of international accounting standards, but rather in the

traditional sense of the process of putting a decision or plan into effect.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Introduction

5

In recent years, the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) has been analysing accounting

issues that could affect financial stability, with a strong focus on their macroprudential

policy implications. Starting in 2017 with the publication of a report commissioned by the

European Parliament on the financial stability implications of IFRS 9 Financial Instruments,

3

the

ESRB has been analysing the expected credit loss approach under IFRS 9, the macroprudential

implications of financial instruments at fair value classified under Levels 2 and 3, and IFRS 17

Insurance Contracts.

4

These publications provide evidence of the interaction between accounting

and financial stability.

In this report, the ESRB analyses how climate-related risks are addressed in accounting

standards and reflected in financial statements, taking a financial stability perspective.

5

In

particular, the report assesses, from a financial stability perspective, whether the current body of

IFRS accounting standards contains adequate requirements and poses no restrictions to reporting

entities in (i) recognising in an adequate and timely manner, (ii) consistently estimating, and (iii)

fully presenting and disclosing the impact of climate-related risks in IFRS financial statements.

6

As

such, the report is limited to IFRS accounting standards and does not, therefore, cover national

accounting standards or address the non-financial part of the annual report. In general, IFRS

financial statements comprise, as a minimum, the statement of financial position (balance sheet),

the statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income for the period, the statement of

changes in equity, the statement of cash flows, the notes, and comparative information as

prescribed by IFRS accounting standards.

7

Aside from the information on climate-related risks

contained in the financial statements, there may be further references to such risks in other parts of

the annual report, such as the management report or the corporate governance statement, which

are not covered by this report.

8

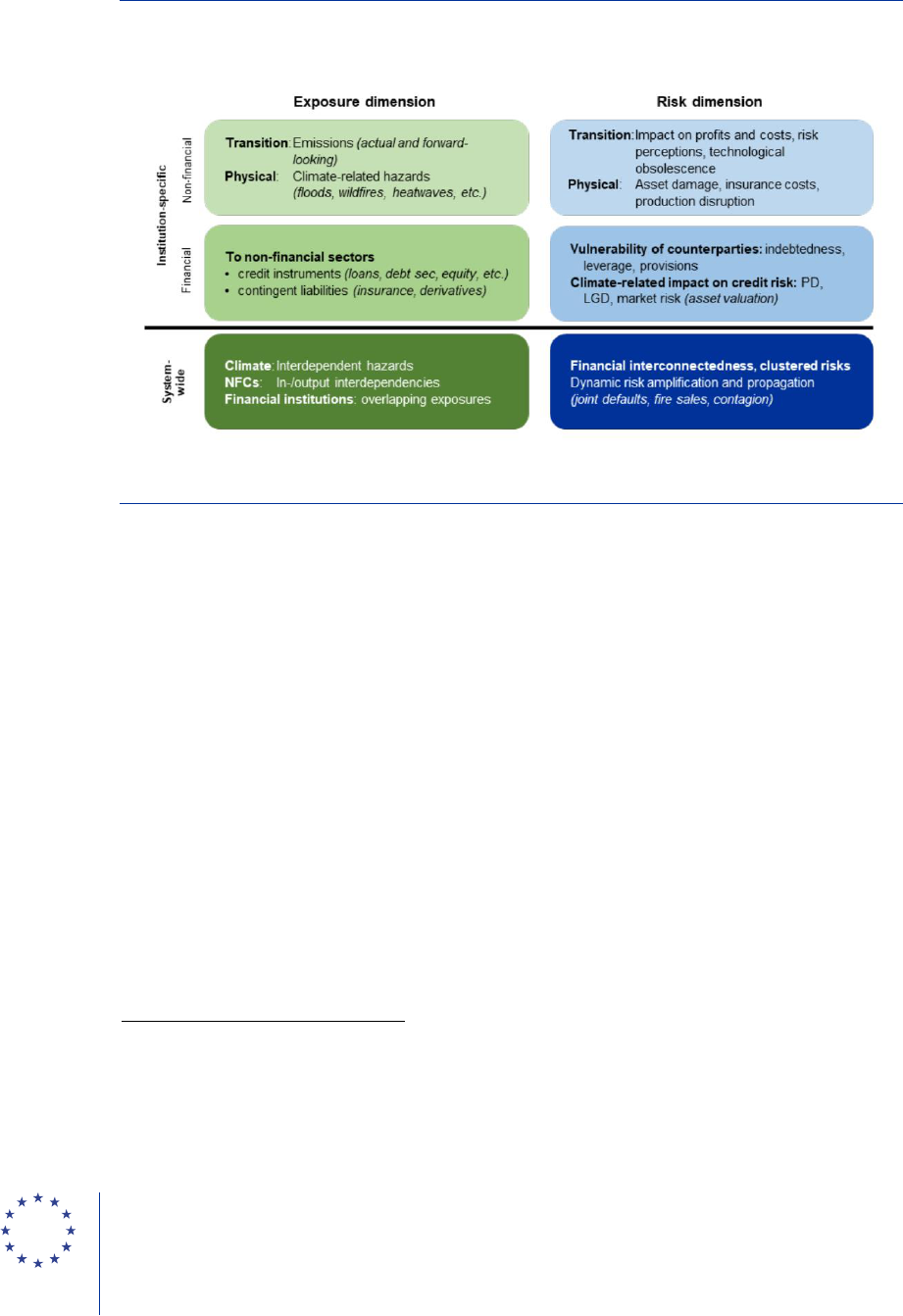

Based on the definitions provided by the Financial Stability Board (2020a), this report

considers both physical and transition risks within the exposure-risk framework as defined

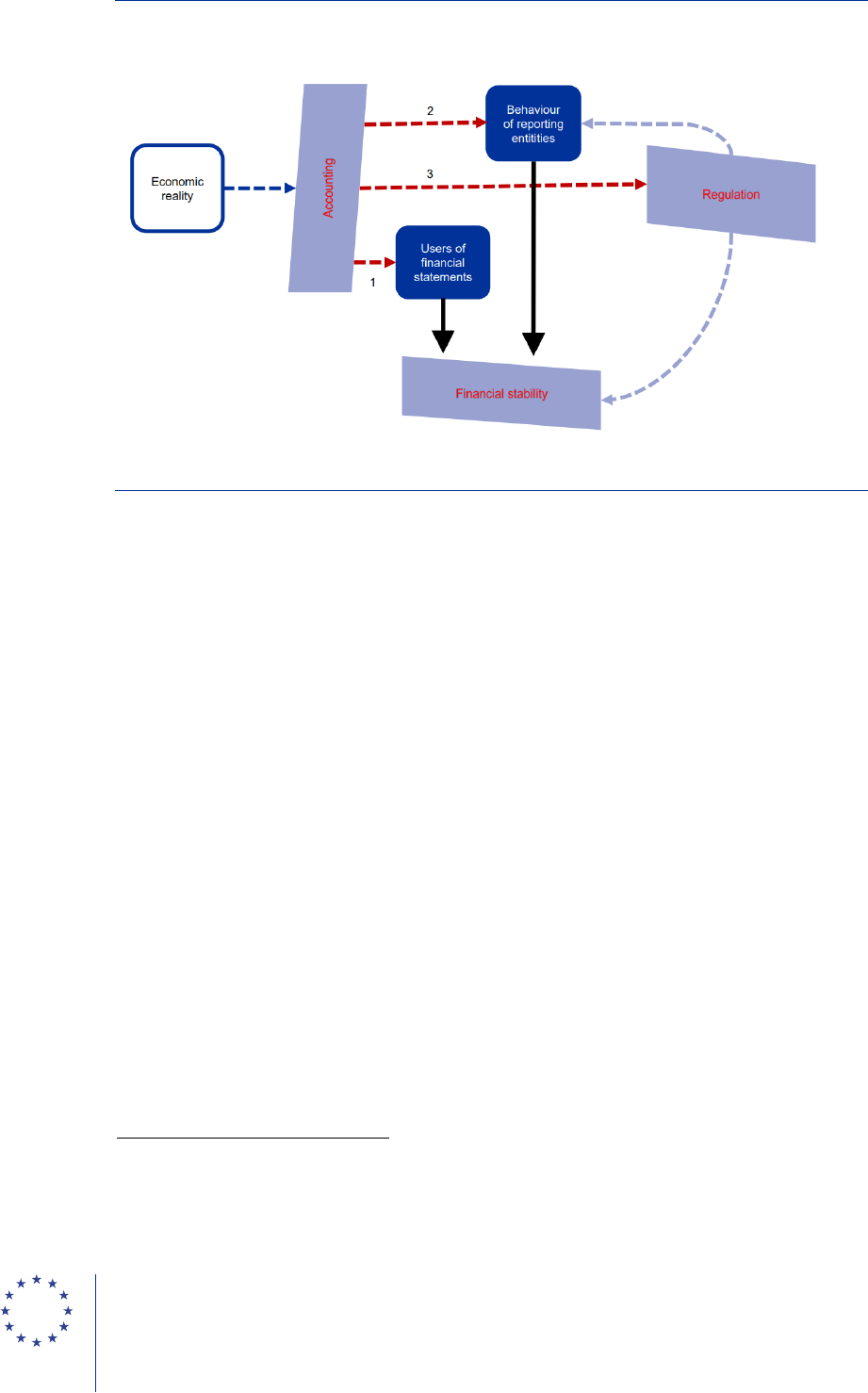

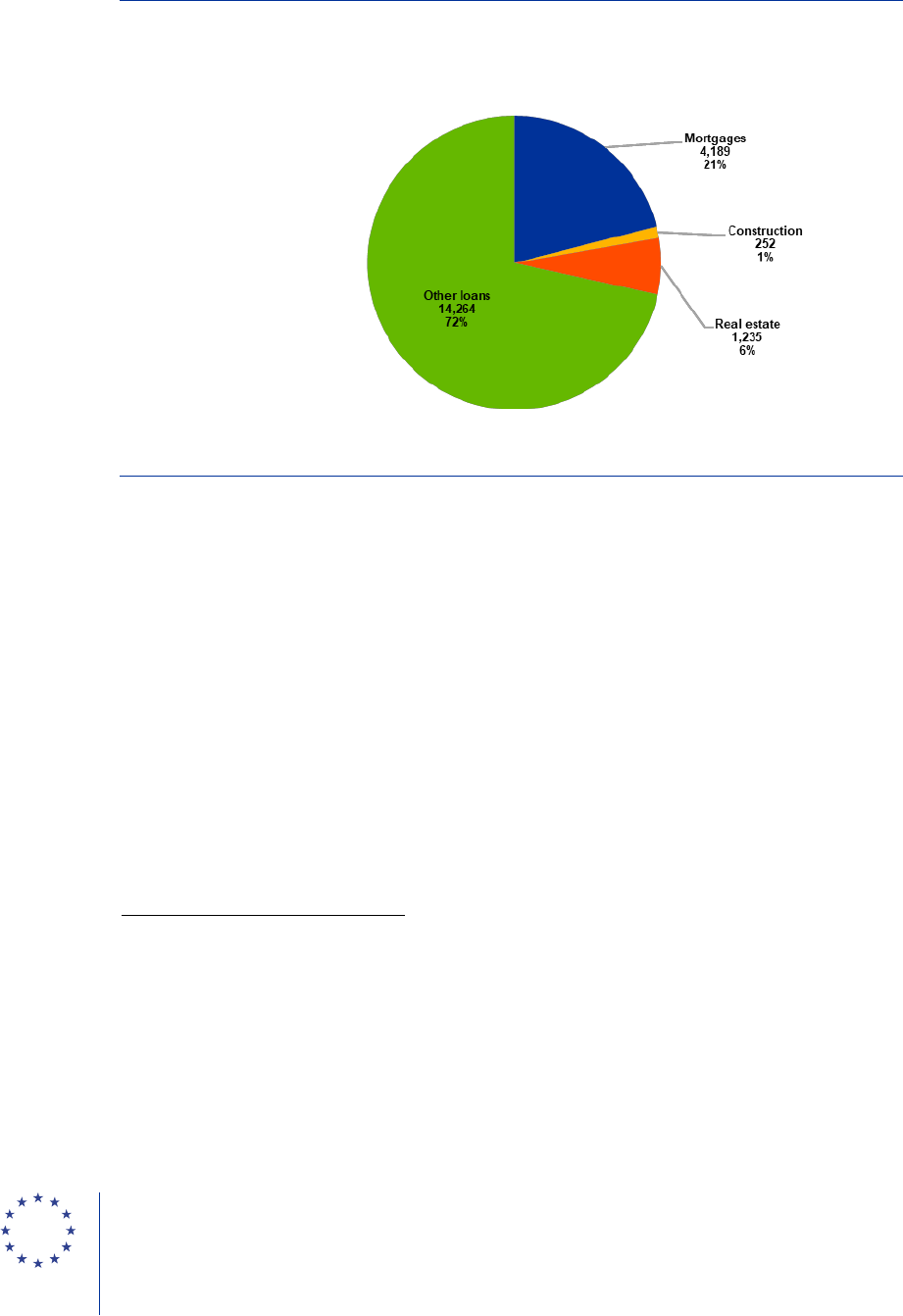

by the ECB/ESRB (Figure 1).

9

The Financial Stability Board (2020a) defines physical risks as the

possibility that the economic costs of the increasing severity and frequency of climate change-

related extreme weather events, as well as more gradual changes in climate, might erode the value

3

See European Systemic Risk Board (2017).

4

See European Systemic Risk Board (2019a, 2019b, 2020a and 2021a).

5

Following the terminology of the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the report uses the term “climate-related risks”. It can be

treated as a synonym of “climate risks”, which is also used in the field.

6

Climate change presents not only risks but also opportunities, although this report focuses on the risks.

7

See IAS 1.10.

8

See Article 19 and Article 20 of Directive 2013/34/EU.

9

These definitions are broadly consistent with those provided by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2021).

According to the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, physical risks are those related to “economic costs and

financial losses resulting from the increasing severity and frequency of: (i) extreme climate change-related weather events

(or extreme weather events) such as heatwaves, landslides, floods, wildfires and storms (i.e., acute physical risks); (ii)

longer-term gradual shifts of the climate such as changes in precipitation, extreme weather variability, ocean acidification,

and rising sea levels and average temperatures (i.e., chronic physical risks or chronic risks); and (iii) indirect effects of

climate change such as loss of ecosystem services (e.g., desertification, water shortage, degradation of soil quality or

marine ecology).” Meanwhile, transition risks are defined as “the risks related to the process of adjustment towards a low-

carbon economy”.

1 Introduction

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Introduction

6

of financial assets, and/or increase liabilities. Transition risks relate to the process of adjustment

towards a low-carbon economy. Physical and transition risks thus defined are placed in an

exposure-risk framework, which identifies system-wide vulnerabilities as well as institution-specific

vulnerabilities (European Central Bank and European Systemic Risk Board, 2022).

Figure 1

Climate-related exposure-risk framework

Source: European Central Bank and European Systemic Risk Board (2022).

This report does not elaborate on potential amendments to the prudential framework to

address the systemic impact of climate-related risks, and nor does it address the interaction

between the prudential framework and accounting. Rather, the scope of this report is limited to

a reflection on climate-related risks in IFRS accounting standards and the resulting financial

statements. Consequently, it does not discuss how the prudential framework could be used by

authorities to prevent or mitigate the financial stability impacts of the materialisation of climate-

related risks.

10

In the EU, there are ongoing discussions on how climate-related risks could lead to

amendments to the capital requirements for banks and insurance corporations (European Banking

Authority, 2023; European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, 2023).

11

While

acknowledging the possible role of prudential regulation, this report does not perform any

comparative analysis on the benefits and costs of using prudential regulation to address climate-

related risks.

The IFRS Foundation, the European Commission and ESMA have been carrying out valuable

work in the realm of accounting and climate-related risks.

12

The International Accounting

Standards Board (IASB) of the IFRS Foundation, which issues IFRS accounting standards and

interpretations thereof, has issued two notes on how climate-related risks might interact with IFRS

10

Recommendations on adequate risk management within financial institutions could also contribute to alleviating the impact

of climate-related risks but are neither the goal of this report.

11

See also European Central Bank and European Systemic Risk Board (2023).

12

See also Martínez and Pérez Rodríguez (2023).

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Introduction

7

accounting standards (Anderson, 2019; International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation,

2023). In March 2023 the IASB launched a project to explore whether and how companies can

provide better information about climate-related risks in their financial statements, and in

September 2023 it initiated targeted actions to improve the reporting of climate-related and other

uncertainties in the financial statements.

13

Moving to the European Union (EU), respondents to a

consultation on the Renewed Sustainable Finance Strategy in 2020 identified several areas in IFRS

accounting standards that could hamper the adequate and timely recognition and consistent

estimation of the impact of climate-related risks, particularly in relation to impairment, provisions

and contingent liabilities (European Commission, 2020). Following on from that consultation, the

European Commission is working with EFRAG (the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group),

ESMA, the IASB and the industry to ensure that financial reporting standards are able to capture

relevant sustainability and climate-related risks. Additionally, the EU Taxonomy Regulation was

adopted in 2020, with the aim of creating a dictionary of activities considered green and effective in

combating “greenwashing” practices. Recently, ESMA has flagged climate-related matters with

regard to financial information as an enforcement priority.

14

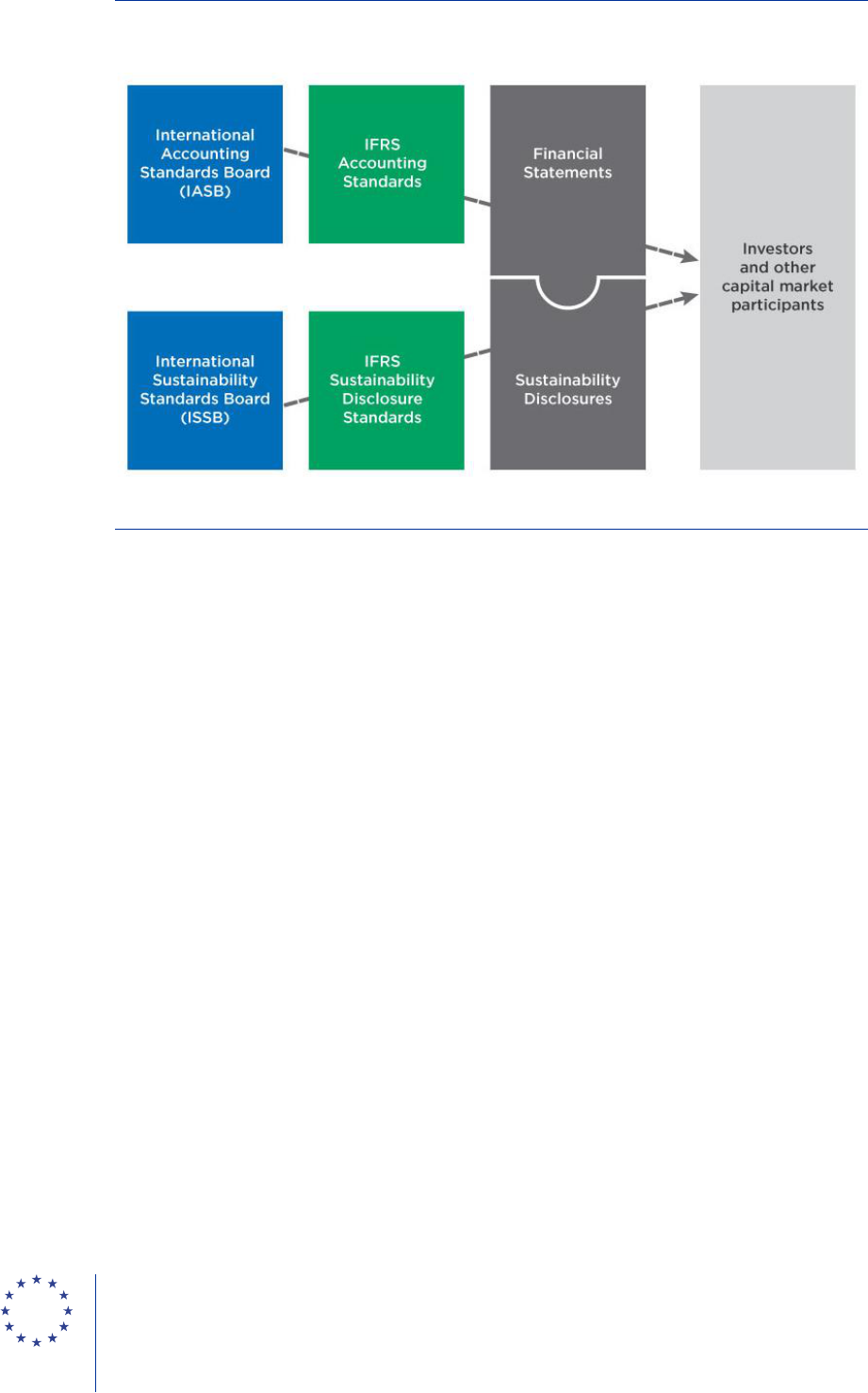

This report does not consider sustainability standards issued by the International

Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) or the European Sustainability Reporting Standards

(ESRS). In November 2021, the IFRS Foundation decided to create the ISSB, to deliver a

comprehensive global framework for sustainability-related disclosures. The IFRS accounting

standards and the IFRS sustainability standards issued by the ISSB should complement each other

to provide investors and other capital market participants with comprehensive information to meet

their needs. In this sense, neither of those sets of standards should be considered in isolation.

ISSB standards relate to disclosures on material sustainability-related financial risks and

opportunities and are not directly drawn from the IFRS accounting framework. On 26 June 2023 the

ISSB issued finalised standards on general sustainability-related disclosure requirements and on

climate-related disclosure requirements.

15

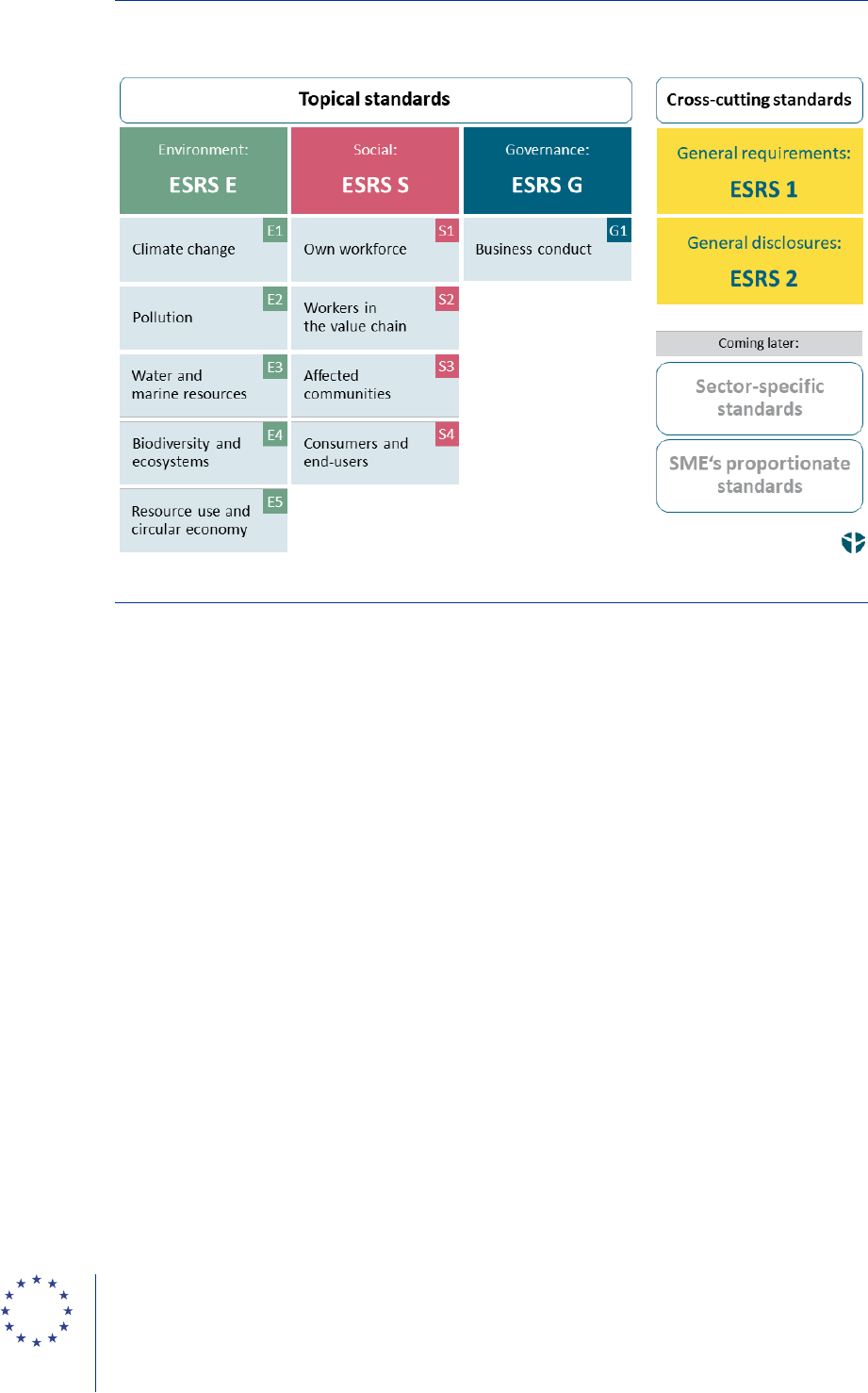

In November 2022 EFRAG issued 12 Exposure Drafts of

ESRS covering environmental, social and governance topics.

16

The Commission adopted the first

set of ESRS as Delegated Acts in July 2023 and published them in December 2023.

17

Annex 2

describes the content of ESRS E1 Climate Change. Further standard-setting activities are ongoing

regarding a second set of ESRS, including sector-specific standards and other standards tailored to

listed small and medium-sized entities, scheduled for June 2024. The ESRS and the first two

standards issued by the ISSB at the global level were developed in parallel and in close

cooperation, resulting in a very high degree of alignment, as evidenced by overlapping sections of

ISSB standards having been integrated into the EU framework.

18

Such alignment does not call into

13

See IASB initiates project to consider climate-related risks in financial statements.

14

Annex 1 describes in further detail the work of ESMA in this area.

15

See ISSB issues inaugural global sustainability disclosure standards.

16

See Public consultation on the first set of Draft ESRS and First set of draft ESRS.

17

See Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 of 31 July 2023 supplementing Directive 2013/34/EU of the

European Parliament and of the Council as regards sustainability reporting standards.

18

See European Commission, Questions and Answers on the Adoption of European Sustainability Reporting

Standards.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Introduction

8

question the consistency of ESRS with the EU’s own legal framework and the objectives of the

European Green Deal, which are broader in scope than the ISSB standards.

19

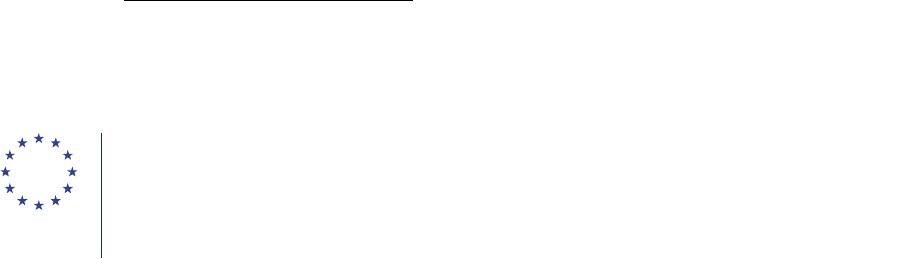

Connectivity between accounting and sustainability standards is important to ensure that

they both contribute to the provision of accurate information to the public. In sustainability

reporting, connectivity refers to the direct connection between sustainability information and

information in the financial statements or the general ledger (EFRAG, 2021).

20

The concept of

connectivity is linked to the provision to the public of a set of coherent and comprehensive

information in the annual report (Figure 2). The sustainability report, which is based on

sustainability standards, should complement and supplement the information contained in the

financial statements, which is based on accounting standards. In the EU context, ESRS 1 General

Requirements calls for reporting entities to connect their sustainability information with the

information they disclose in the financial statements.

21

More precisely, ESRS E1 Climate Change

requires a reconciliation of assets and net revenue linked to material physical risks to specific line

items in the financial statements.

22

This is one of the differences between IFRS S2 Climate-related

Disclosures (issued by the ISSB) and ESRS E1, as IFRS S2 does not have a similar requirement.

Connectivity should also prevent overlap of information in different parts of the annual report

(EFRAG, 2021).

23

A lack of connectivity between sustainability and accounting information can

diminish transparency, with potentially adverse impacts on the credibility of the information

disclosed, thus weakening market trust.

19

For more information on the European Green Deal, see The European Green Deal – Striving to be the first climate-

neutral continent.

20

While this could be defined as “direct” connectivity, it would also be possible to define “indirect” connectivity as referring to

sustainability disclosures that cannot be directly reconciled to the financial statements or accounting estimates in the

current period (EFRAG, 2023).

21

See Section 9.2 of ESRS 1 General Requirements.

22

See paragraph 68 and paragraphs AR77 to AR79 of ESRS E1 Climate Change.

23

Some degree of overlap may, however, be unavoidable, given that each set of standards has to stand on its own.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Introduction

9

Figure 2

International accounting and sustainability standards

Source: IFRS Foundation.

This report is organised as follows. Section 2 provides further methodological considerations on

how accounting can reflect climate-related risks and discusses channels through which the related

estimates could have an impact on financial stability. Section 3 presents the four main issues

identified for financial stability. Section 4 concludes by discussing potential policy actions to

address the issues identified.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Conceptual and methodological considerations

10

This section of the report outlines several important conceptual and methodological

considerations in the analysis of how accounting is able to reflect climate-related risks and

how this could affect financial stability. Subsection 2.1 below discusses the boundaries of

financial reporting, in relation to the events and transactions that lead to the recognition of an asset,

liability, income or expense (or a gain or loss). The section continues with a discussion of the

channels through which accounting can affect financial stability, focusing on climate-related risks.

2.1 The boundaries of financial reporting

At a conceptual level, climate-related risks can have accounting impacts and can also affect

the relevance, reliability and materiality of the information disclosed in the financial

statements. Accounting can be seen as a process starting with a set of definitions, recognition

criteria and measurement concepts, based on which accounting policy choices and judgements are

then made and applied in order to produce the estimates that ultimately result in the financial

statements. Climate-related risks can potentially affect accounting policy choices (e.g., when

accounting for emissions and pollutant pricing mechanisms), judgements (e.g., on impairment) or

estimations (e.g., of expected credit losses), as well as the criteria for the recognition and

measurement of assets and liabilities (e.g., adjustments to the useful life of assets, or liabilities

related to environmental damage). Decisions on the materiality of certain transactions can also be

affected by the expectations of users of financial statements or practices among peers, which may

render certain disclosures material, even if there are no quantified changes.

Only economic events and transactions that meet the definition of an asset, liability, income

or expense are reported in the financial statements. According to the conceptual framework for

financial reporting, the objective of financial statements is to provide financial information about the

reporting entity’s assets, liabilities, equity, income and expenses that is useful to users of financial

statements. An asset is defined as an economic resource controlled by the entity as a result of past

events, whereas a liability is a present obligation of the entity to transfer an economic resource as a

result of past events. Meanwhile, income and expenses are changes in assets and liabilities that

affect the net residual interest in the entity.

Therefore, the impacts of climate-related risks are included in the financial statements to the

extent that they meet the recognition criteria set out in IFRS accounting standards. Following

the definitions of physical and transition risks by the Financial Stability Board (2020a), physical risks

include, for instance, economic losses from natural catastrophes that have become more likely or

more severe due to the effects of climate change. Such losses can be reflected in the financial

statements to the extent that (i) they have already occurred and affect the existing rights and

obligations of an entity, or (ii) their increased severity or frequency affects the economic benefits

expected from the entity’s existing rights (for instance by reducing the useful life of property and

equipment) or future transfers arising from existing obligations (for example, natural catastrophes

2 Conceptual and methodological

considerations

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Conceptual and methodological considerations

11

may increase the costs that the entity will incur to settle its obligations under an existing contract).

In contrast, recognition criteria preclude the financial statements from capturing the costs

necessary for an entity to mitigate and adapt its activities to climate-related hazards until the point

where it enters a legally binding commitment or has no practical ability to avoid its responsibility.

Similarly, financial statements do not provide information on how those hazards affect the margins

expected by the entity from new contracts entered into in the future. With regard to transition risks,

shifts in policies, technological changes and changes in customer behaviours may affect the

economic benefits that the entity expects to recover from its existing rights and should, therefore,

be reflected in the valuation of its assets in the statement of financial position. However, such

changes may also affect the entity’s ability to continue carrying on its activities in the future (i.e., as

a going concern). Furthermore, shifts in policies are “recognised” on the liability side of the financial

statements only once they are verified (e.g., when new legislation is enacted).

24

As a result, the

“going concern assumption” enshrined in the IASB Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting

could come under scrutiny, potentially leading to a different measurement approach being applied

to certain items of the financial statements.

Consequently, fully capturing the long-term financial impacts of climate-related risks cannot

be achieved through accounting or sustainability reporting alone (Figure 3). Information

about an entity’s exposure to climate-related risks can only be partially addressed through

accounting. Even when designed and implemented optimally, accounting standards may not be

enough in themselves to obtain a comprehensive and accurate view of the exposure, given the

long-term and largely uncertain nature of climate-related risks. In particular, financial statements

may not adequately reflect (i) risks that materialise beyond the time horizon over which the entity

expects economic benefits from its assets and cash outflows to settle its liabilities, and (ii) the future

actions that an entity may be compelled to take in order to mitigate and adapt to climate-related

risks and continue to operate as a going concern. In other words, when accounting pays too much

attention to future events, it can become less reliable and less robust; in turn, when it disregards

future events entirely, it may not adequately represent the reporting entity’s financial position. To a

certain extent, this limitation explains why the EU and the IFRS Foundation have adopted

sustainability reporting standards, which are designed to complement financial reporting by

providing information about how sustainability matters (including climate change) affect the entity’s

activities, performance, risks and long-term value. Connectivity between both sets of information is

key to the optimal disclosure of climate-related risks.

24

Similarly, for liabilities associated with climate-related litigation arising from legislation, in many cases sufficient evidence

would not arise until the new legislation is enacted (or is close to being enacted).

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Conceptual and methodological considerations

12

Figure 3

Climate-related risks, accounting and sustainability reporting

Source: Own illustration.

Lastly, uncertainty about the future impact and timing of the materialisation of climate-

related risks is an important factor to consider when assessing how accounting may reflect

such risks. At this point, it is important to draw a distinction between “risk” and “uncertainty”: risks

are in principle measurable (as the probabilities and possible outcomes are objectively or

subjectively determinable) and, as long as they have a monetary or financial effect on the reporting

entity, should be reflected in the financial statements, while uncertainty can at best be estimated as

no probability can be reliably associated to any possible outcome. The prevailing uncertainty

surrounding the timing and extent of the materialisation of climate-related risks can affect the

assessment of an entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. Furthermore, bringing climate-

related risks into the financial statements may add complexity to several estimations, ranging from

impairment testing to expected cash flows, risk adjustments to the discount rates or expected credit

losses. Although IFRS accounting standards require forward-looking estimates of variables that

affect the assets and liabilities reported in the financial statements at the end of the reporting

period, these estimates should be disclosed over a short-term horizon only: the next financial year.

In fact, IAS 1.125 requires that the entity’s assumptions about the future and other major sources of

estimation uncertainty be disclosed only if the referred variables “have a significant risk of resulting

in a material adjustment to the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities within the next financial

year”. Consequently, the financial impact of climate-related risks over the longer term may not be

captured in a company’s financial statements.

2.2 Climate-related risks, accounting and financial stability

Accounting can be seen as a process of conveying the impact of economic events and

transactions to users of financial statements. Based on conceptual foundations around the

notions of assets, liabilities, equity, income and expense, accounting standards define the

principles building on which economic phenomena are presented to users of financial statements in

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Conceptual and methodological considerations

13

order to inform their decision-making in a relevant and reliable way.

25

Inspired by those principles,

management of reporting entities defines the accounting policies and measurement assumptions

relied on in determining the estimates set out in the financial statements. The information contained

in the financial statements should then provide decision usefulness, in the sense that it can be used

by the public to make qualified and educated opinions on the reporting entity.

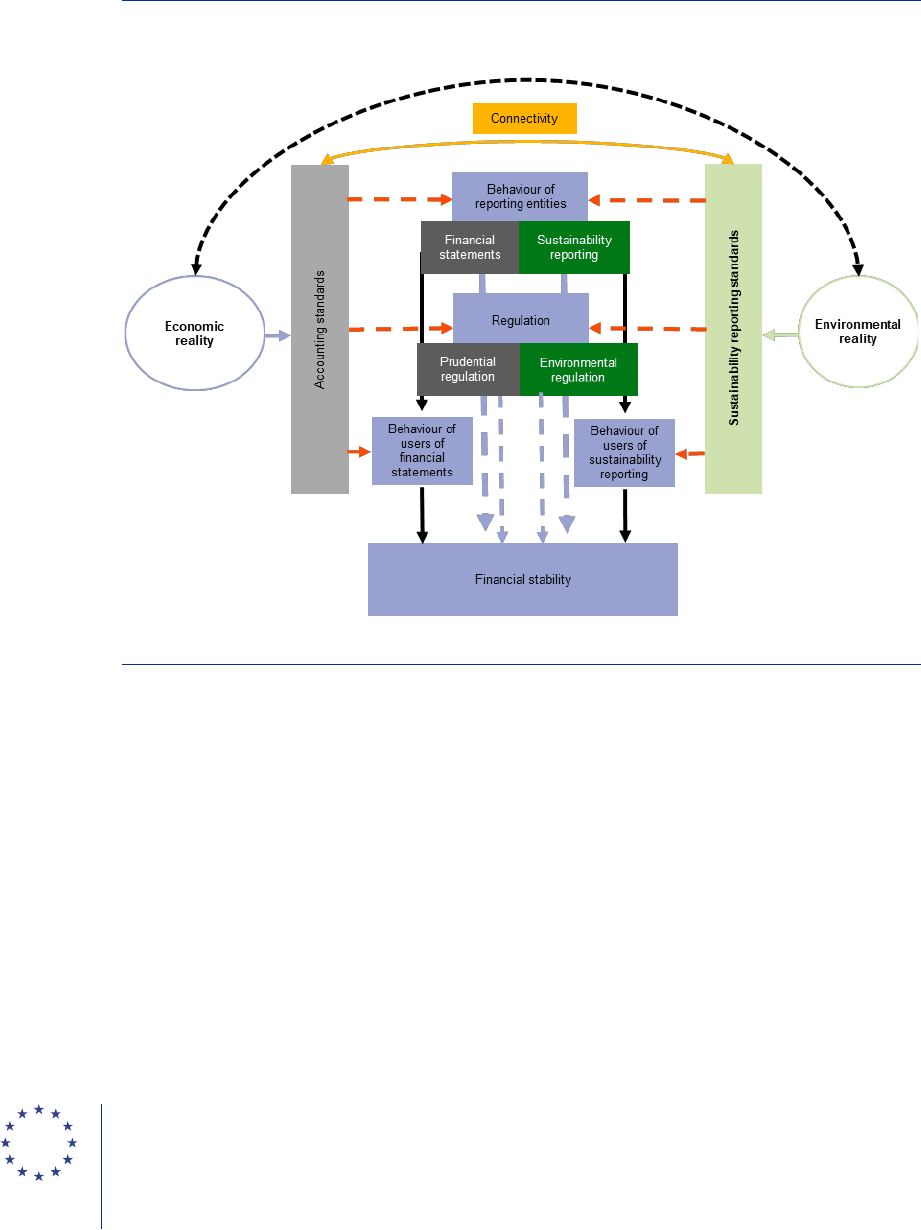

Although the accounting process is not primarily meant as a tool to foster financial stability,

there are at least three channels through which relevant and reliable financial information

resulting from this process can be beneficial to financial stability: through transparency

(channel 1 in Figure 4); through the behavioural response of economic agents to accounting

information (channel 2 in Figure 4); and through regulation (channel 3 in Figure 4). First,

transparency in accounting, understood as access to relevant, reliable, comprehensive and timely

financial information about an economic agent, enables users of financial statements to make

informed decisions of an economic nature. It promotes market discipline, which discourages

reporting entities from engaging in risky behaviours and transactions and supports efficient

allocation of resources. Transparency would thus be linked to the concept of “true and fair view”,

according to which the financial statements should not contain falsehoods (i.e., be true) and should

accurately report the condition they wish to portray (i.e., be fair). Second, even if theoretically

accounting standards should be neutral for economic decision-making, in practice they may also

incentivise certain behaviours among economic agents, which may, in turn, give rise to financial

stability concerns. Lastly, accounting is either the starting point or key reference when defining

prudential requirements for regulated financial institutions, thus affecting their solvency and liquidity

picture.

If markets function properly and information on risks is adequately incorporated into the

financial statements, the pricing of different assets should adjust accordingly and no

financial stability concerns should arise. This illustrates the crucial importance of properly

accounting for risks in the financial statements. In the absence of such proper accounting, either

one or all of those three transmission channels could be activated by a sudden reassessment of

investor expectations that forces abrupt adjustments in the financial statements (i.e., an

“information shock”). Those shocks could potentially affect financial stability through a combination

of fire sales, higher cost of capital and suboptimal allocation of resources.

26

25

In other words, accounting comprises the processes whereby business activities and commercial transactions are

accounted for, together with the economic impacts relevant for their respective measurement.

26

As explained by Pérez Rodríguez (2021), information shocks tend to follow episodes of unanticipated corporate failure

associated with irrational balance sheet expansions, and their negative externalities are usually felt in the form of higher

costs of capital being imposed on reliable and unreliable companies alike.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Conceptual and methodological considerations

14

Figure 4

Accounting and financial stability

Source: European Systemic Risk Board (2021).

In the case of climate-related risks, “information shocks” and, more broadly, a lack of

relevant and reliable financial information, could affect financial stability through the three

transmission channels described above. In terms of transparency, accounting information that

misstates the value of assets or liabilities, does not appropriately reflect the accrual of income or

expenses, or fails to recognise gains or losses in timely fashion can lead users of the financial

information to make suboptimal economic decisions. This would be the case where climate-related

risks are not incorporated into the valuation of assets or liabilities, but also if poor disclosures are

provided regarding the assumptions on how the reporting entity might be affected by those risks. In

any of those cases, overestimation of assets, anticipation of income or gains, underestimation of

liabilities, or deferral of expenses or losses could result in large adjustments if and when the risks

materialise, especially where such risks are highly uncertain and/or have long horizons. Regarding

the behaviour of reporting entities in response to how accounting reflects climate-related risks,

certain types of responses would be detrimental to financial stability, such as delays in recognising

certain liabilities or expenses arising from environmental considerations, concentration of

exposures to certain asset types that receive a more favourable accounting treatment in

comparable terms,

27

or underestimation of the impact of climate-related risks on the balance sheet

and statement of profit or loss. A generalised, inaccurate reflection of climate-related risks in the

financial statements of reporting entities could lead economic agents to base their economic

decisions on suboptimal information. Lastly, the inclusion in regulatory calculations of accounting

information not appropriately reflecting climate-related risks could hamper the assessment by

regulatory and supervisory authorities of the solvency and liquidity of the reporting entity. For

instance, not incorporating climate-related risks into the expected credit loss model under IFRS 9,

27

For example, this could occur in the case of certain assets measured at cost, for which the impairment test does not

sufficiently take into account climate-related risks, while assets at fair value would already incorporate climate-related risks

in their market values.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Conceptual and methodological considerations

15

or into the IRB model parameters, could affect the determination of capital requirements for banks.

In all those cases, financial stability could be affected by an information shock and the ensuing

adjustments could trigger widespread divestment in certain sectors and activities, a rebalancing of

positions, and potentially significant movements in holdings of financial assets among market

participants.

While financial institutions may not be largely exposed to physical or transition risks

directly, their interactions with the real economy indirectly expose them to climate-related

risks, the materialisation of which can have financial stability implications. Looking at the

definitions of physical and transition risks used in this report, the financial stability implications of

direct exposures to these risks among financial institutions should be rather limited. However,

through their exposures to the real economy in the form of loans, real estate collateral, insurance

contracts or holdings of securities, they may be indirectly affected by climate-related risks. The way

in which these risks are reflected in the financial statements may raise financial stability concerns.

For example, climate-related risks could affect the value of real estate and similar immovable

assets, and significantly affect banks and other financial institutions through large direct or indirect

exposures (e.g., via real estate funds or securitisations). Similarly, a sudden and substantial

deterioration in the quality of bank loan books, as a result of climate-related risks not adequately

reflected in their value, could lead to deleveraging and a procyclical retrenchment in credit activity.

This could also trigger credit rating downgrades, higher credit spreads and, more broadly, a loss of

trust across financial institutions and their customers, with further contagion and spillover effects.

28

Similarly, failure to timely incorporate climate-related risks in the fair value of financial instruments

could trigger large sudden decreases in their fair value, which, if held by banks or insurance

corporations could trigger fire sales of assets and affect the availability of credit and insurance

services.

29

The emergence of large unrecognised losses from climate-related factors not

considered when estimating the technical provisions of existing insurance contracts (such as home

insurance policies) is another example of the type of information shock that could affect financial

stability if accounting standards are not properly implemented, thus leading to suboptimal financial

statements.

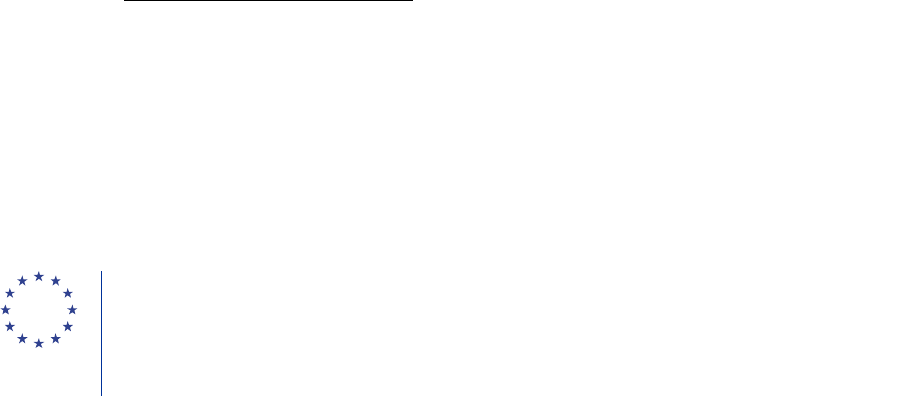

The interactions between the financial system and non-financial corporations in considering

and recognising the impact of climate-related risks, needs to be expanded, to take into

account the environmental reality and the related sustainability standards (Figure 5). As

shown in Figure 5, the environmental reality interacts with the economic reality and is the object of

sustainability reporting standards. At this stage, connectivity between accounting and sustainability

reporting standards is of paramount importance, as users of financial information and sustainability

reports may otherwise receive contradicting information on the same reality. For example, when

sustainability reporting explains the physical or transition risks arising from an entity’s activities and

its assets and liabilities, such disclosures could be linked to the corresponding provisions that

would be required in the financial statements. Sustainability disclosures may also provide early

indications of matters that could subsequently be reflected in the financial statements (for instance,

a commitment to net zero emissions could, over time, result in liabilities being reported in the

financial statements). Accounting and sustainability information should, in conjunction, provide a

28

This would be the case for loan portfolios used as collateral for collateralised loan obligations (CLOs).

29

In the case of securitisations, collateralised debt Obligations (CDOs) could also be materially affected.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Conceptual and methodological considerations

16

holistic, comprehensive and coherent picture of the climate-related risks faced by the reporting

entity and their expected impact. Conversely, the use of disconnected information for prudential

and environmental regulatory purposes could lead to inconsistencies. Reporting entities could also

decide to favour disclosures in either the financial statements or in sustainability reporting, to suit

their own objectives. A lack of connectivity between these two reflections of similar realities would

certainly lead to a suboptimal provision of information to the public, potentially hampering the

proper functioning of financial markets when it comes to risk pricing and the allocation of financing

activities and capital flows from investing.

Figure 5

Accounting, sustainability reporting and financial stability

Source: Own illustration.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Main issues identified

17

A subset of IFRS accounting standards have been identified as being more closely related

to climate-related risks. Based on other assessments (Anderson, 2019; European Commission,

2020; International Financial Reporting Standards, 2020) and on expert judgement, the following

IFRS accounting standards have been identified: IAS 1 Presentation of Financial Statements, IAS 2

Inventories, IAS 8 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors, IAS 16

Property, Plant and Equipment, IAS 36 Impairment of Assets, IAS 37 Provisions, Contingent

Liabilities and Contingent Assets, IAS 38 Intangible Assets, IAS 40 Investment Property, IAS 41

Agriculture, IFRS 6 Exploration for and Evaluation of Mineral Resources, IFRS 7 Financial

Instruments: Disclosures, IFRS 9 Financial Instruments, IFRS 13 Fair Value Measurement, and

IFRS 17 Insurance Contracts.

From an in-depth analysis of these IFRS accounting standards, the ESRB has identified four

main issues of relevance for financial stability. They refer to (i) the extent to which market

prices – and hence fair values of Level 1 and Level 2 financial assets or the discount rates used to

compute present values – incorporate climate-related risks, both physical and transition; (ii) the

effect of such risks on the initial and subsequent valuation of non-financial assets and liabilities,

including property, plant and equipment, intangibles, goodwill, provisions and contingent liabilities;

(iii) the incorporation of climate factors into the models used by preparers of financial statements,

including factors affecting expected cash flows, risk adjustments to the discount rates for insurance

liabilities or the estimation of expected credit losses from financial assets at amortised cost (e.g.

loans); and (iv) disclosures. The following subsections explore these issues in further detail, while

Table A1 in Annex 3 lists the IFRS accounting standards most closely linked to them.

30

The order in

which the four issues are presented does not imply any prioritisation or ranking.

3.1 The extent to which market prices incorporate climate-

related risks

The incomplete incorporation of climate-related risks in market prices can cause assets to

be overestimated or liabilities to be underestimated.

31

Several IFRS accounting standards rely

on market prices for the purpose of valuing assets and liabilities. Examples here include financial

assets at fair value and, optionally, tangible assets and investment property or the discount rates

applied when measuring insurance liabilities.

32

It also holds true for the initial measurement of

acquired assets, as cost is equivalent to fair value at the time of acquisition. If these assets and

liabilities are directly or indirectly affected by climate-related risks but their market prices (or,

30

Neither the four issues identified nor the related IFRS accounting standards are exhaustive.

31

Market prices simply reflect prices of actual (or potential) transactions and may be under- or overestimating some risks.

Ideally, all relevant risks, including climate-related risks, should be incorporated into the market price of an asset. This is

the approach taken in the following paragraphs, which should not be seen as calling for a correction of market prices to

incorporate climate-related risks.

32

When measuring insurance liabilities, IFRS 17 requires the discount rates to be market consistent and to reflect the

characteristics of the liability. That would imply eliminating any “climate-related risk premium” implicit in the fair value of the

reference portfolio of assets when determining the discount rate. For further details on the computation of discount rates

under IFRS 17, see European Systemic Risk Board (2021).

3 Main issues identified

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Main issues identified

18

alternatively, the discount rates) do not fully reflect such risks, financial statements could potentially

lead to suboptimal economic decisions.

33

Furthermore, failing to incorporate climate-related risks in

market prices could also hamper the accuracy of computed liquidity premia.

Not incorporating climate-related risks in the market prices of financial instruments would

affect their fair values, as well as provisions or tangible assets measured at fair value and

exposed to climate-related risk factors.

34

Banks, insurance corporations, pension funds and

investment funds can be affected through their holdings of equity instruments (including investment

fund shares) and debt securities. While not in the aggregate, certain non-financial corporations may

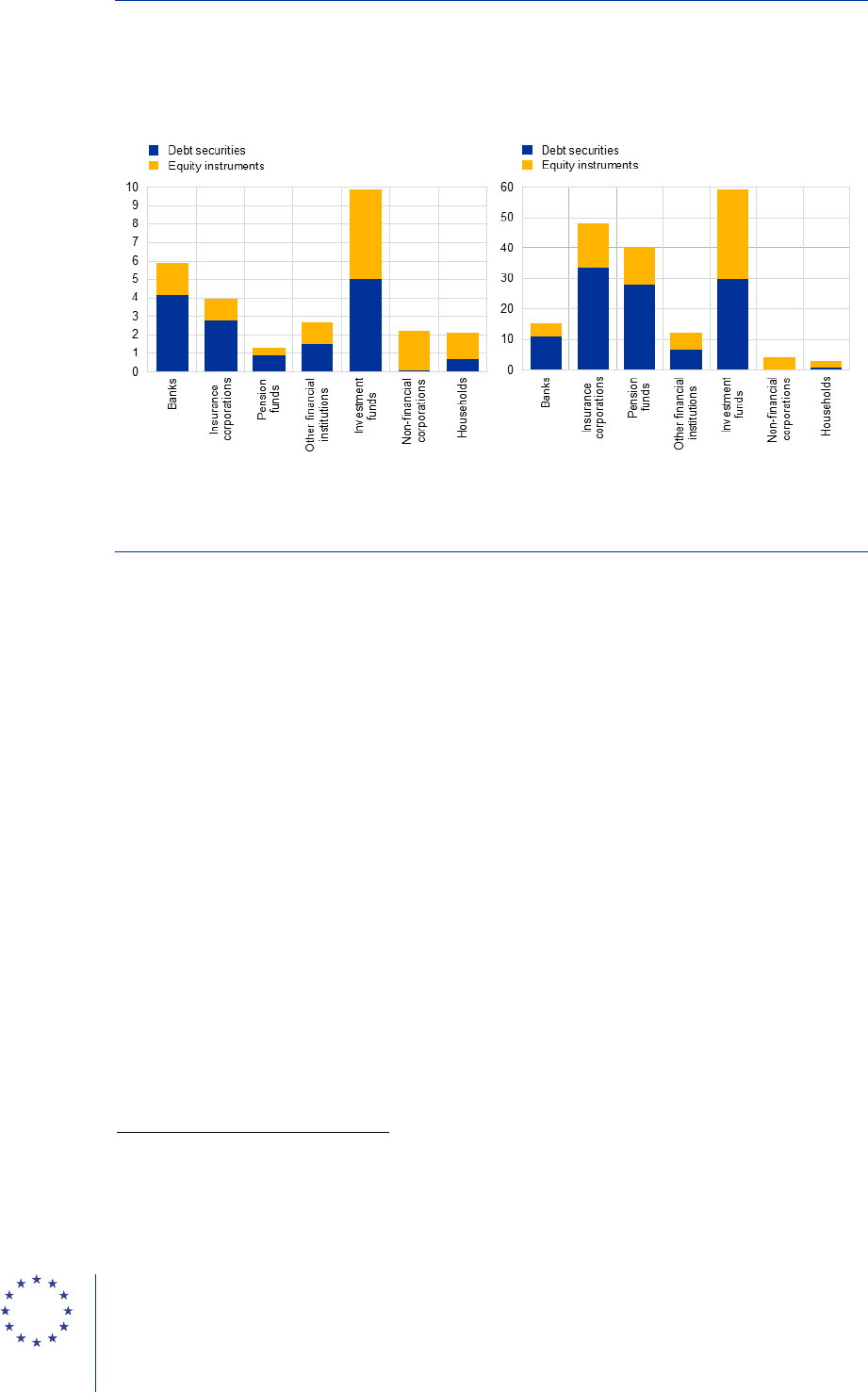

also be affected to the extent that they hold financial assets on their balance sheet. As shown in

Chart 1, which reflects data from the Quarterly Sector Accounts, holdings of debt securities and

equity instruments in the euro area amount to more than €25 trillion, representing around 50% of

total assets in some institutional sectors. On top of that, non-financial corporations that opt for the

revaluation model for their property, plant and equipment or measure investment property at fair

value would also be affected,

35

although there is sparse evidence of the extent to which such a

measurement basis is actually applied among EU non-financial corporations. Christensen and

Nikolaev (2013) find that only 3% of the 1,539 non-financial corporations included in their sample

and domiciled in the United Kingdom and Germany use fair value for non-current assets after their

first-time adoption of IFRS. Investment property represents a small share of the aggregated

balance sheet of EU non-financial corporations (2.4% at the end of 2021, according to the ERICA

database of the European Committee of Central Balance Sheet Data Offices) and is often

measured at fair value, particularly by real estate non-financial corporations (Olante and Lassini,

2022).

36

33

For example, certain climate-related factors (such as high locked-in greenhouse gas emissions) may not be reflected in the

market price as of the acquisition date, thus affecting the asset’s initial measurement. Moreover, given the long-term

horizon over which climate-related risks materialise, it may be the case that the market price of certain short-term financial

instruments is not affected by those risks.

34

IFRS require the fair value of certain non-financial assets measured at amortised cost, such as investment property, to be

disclosed in the notes to the financial statements.

35

Assets measured at amortised cost could potentially be affected as well, in case their market value revealed a substantial

decline in their recoverable amount, which would lead to the recognition of significant impairment losses.

36

For further information on the ERICA database, see ECCBSO – Erica Working Group.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Main issues identified

19

Chart 1

Debt securities and equity instruments held by euro area institutional sectors, Q2 2023

a) Total volume

b) Share of total assets of each sector

(EUR trillions)

(percentages)

Sources: ECB and ESRB Secretariat calculations.

Notes: Information based on the System of National Accounts. The sectors of rest of the world, money market funds,

government and central banks are excluded.

Regardless of the above considerations, the inclusion of climate-related risks in the market

price of certain assets is a matter that goes beyond the accounting realm. Given that fair

value is understood as an exit price, i.e., the price at which an asset would be transferred (or a

liability assumed) between knowledgeable parties not forced to transact, accounting standards

typically take market prices as a proxy for fair value. In that sense, the fair value of an asset is

based on assumptions and methodologies developed by market participants and therefore reflects

a “consensus” within a market at a point in time. For financial assets in Level 1 and, to a certain

extent, in Level 2, fair value can be considered an objective measure, free from management

influence.

37

The underlying assumption is that market prices incorporate the significant risks to

which the asset is exposed, though these prices may not fully incorporate all externalities related to

the underlying asset. In these situations, accounting standards do not usually provide an alternative

measurement criterion that can replace or adjust the asset’s fair value or, in the case of traded

financial instruments, such alternative measurement criterion may not be preferable. There have

been recent discussions on the extent to which climate-related risks are incorporated into the

market prices of a wide variety of assets (European Systemic Risk Board, 2020b; Basel Committee

on Banking Supervision, 2021).

38

Even if this is a matter that goes beyond the accounting realm,

accounting standard-setters have not questioned the reliance on fair value (subject to the

necessary adjustments) to measure assets and liabilities in those cases. Eren et al. (2022) provide

a summary of the findings in the academic literature on the same topic, revealing an incomplete

and imperfect view of how market prices reflect climate-related risks. Stroebel and Wurgler (2021)

37

For further information on the fair value hierarchy, see European Systemic Risk Board (2020a).

38

See HSBC's Stuart Kirk tells FT investors need not worry about climate risk for a controversial contribution to the

discussion.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Main issues identified

20

conducted a survey among 861 finance academics, professionals, public sector regulators and

policy economists, with most respondents believing that asset prices underestimate climate-related

risks.

Although the expectation would be for market prices to gradually incorporate climate-

related factors, a scenario of sudden adjustment cannot be completely ruled out. While the

transition to a low-carbon economy is likely to unfold over time and the current uncertainty around

the physical impacts of climate change should gradually dissipate, we cannot rule out scenarios

involving a sudden and disorderly transition or, as a result of non-linearities, a sudden and abrupt

materialisation of the physical impacts of climate-related risks. Such scenarios could lead to large

and abrupt shifts in market expectations, driving substantial changes in market prices, large

revaluations or adjustments to the carrying amounts, and the accompanying losses. Either because

of correlated exposures and herd behaviour, or as a result of counterparty risk and contagion given

the significant interconnections existing within the financial system, this may simultaneously affect a

large group of financial institutions, with the resulting adverse consequences for financial stability.

39

However, the information available to financial market participants on the exposure to climate-

related risks is expected to improve with the adoption of ESRS and ISSB standards, likely reducing

the probability of a sudden incorporation of climate-related risks into the price of financial

instruments. Meanwhile, the adoption of the ESAP (European Single Access Point) Regulation may

also make it easier for market participants to collect and process information electronically, which

could help in better pricing climate-related risks.

40

3.2 The valuation of non-financial assets and liabilities

Failing to fully include relevant climate-related risks in impairment tests for non-financial

assets may affect their valuation. The valuation of certain categories of fixed assets (such as

those accounted for under IAS 16 Property, Plant and Equipment, IAS 40 Investment Property, IAS

41 Agriculture or IFRS 6 Exploration for and Evaluation of Mineral Resources) may be affected by

climate-related risks (specific examples include machinery that fails to comply with certain pollution

regulations, goodwill that fails to take on board the impact of physical or transition risks on the

expected cash flows of the acquired business, land used for agricultural activities affected by

heatwaves, or buildings with a low energy performance). These assets are typically accounted for

at cost in the balance sheet of non-financial corporations, and are therefore subject to impairment

under IAS 36 Impairment of Assets.

41

According to IAS 36, entities must compare the carrying

amount of assets with their recoverable amount (defined as the higher of fair value less costs of

disposal and value in use) and recognise an impairment loss if the recoverable amount is below the

carrying amount. With the exception of goodwill and certain intangible assets for which an annual

impairment test is required, entities are required to conduct impairment tests whenever there is an

indication of asset impairment.

39

Furthermore, recent developments in energy derivatives markets show how non-financial corporations are increasingly

participating in these markets.

40

See Easy access to corporate information for investors: Provisional agreement reached on the European Single

Access Point (ESAP).

41

Fair value less costs of sale is the preferred valuation method under IAS 41, although cost less accumulated depreciation

and impairment must be used when fair value measurements are unreliable.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Main issues identified

21

Where relevant, non-financial corporations should incorporate climate-related factors into

the impairment tests, even if these factors are not explicitly mentioned in IAS 36. In

particular, value in use is a forward-looking estimate that reflects an entity’s expectations about

future cash flows over the lifetime of the assets, and therefore relies fully on management

expectations. While there is no explicit guidance to incorporate climate-related risks in the

estimation of an asset’s value in use, the time horizon for developing explicit assumptions about

future cash flows is usually limited to five years (see IAS 36.33.b), and beyond this time horizon

entities should use a long-term growth rate to infer expected cash flows over the lifetime of the

assets. Consequently, the incorporation of climate-related risks in the value in use of an asset

subject to impairment depends on the accounting policies, judgements and assumptions made by

each entity, which can lead to inconsistent measurement and impaired comparability in the cross

section.

A scenario of sudden realisation of risks could critically affect the corporate sector, as well

as the banking sector through lending exposures. It would be reasonable to expect a gradual

adjustment over the years of the carrying amount of non-financial assets subject to significant

climate-related risks, through appropriate and timely impairment charges. However, it is also

possible that the process may not run smoothly system-wide, with asset values not being adjusted

over time, thus leading to a sudden drop in value.

42

If the related losses came to affect the financial

position of a broad enough group of non-financial corporations representing a large share of banks’

loan portfolios, there could be a surge in credit losses and a rapid deterioration in the banking

sector’s solvency.

Looking at the aggregate balance sheet of the euro area banking system, loans to sectors

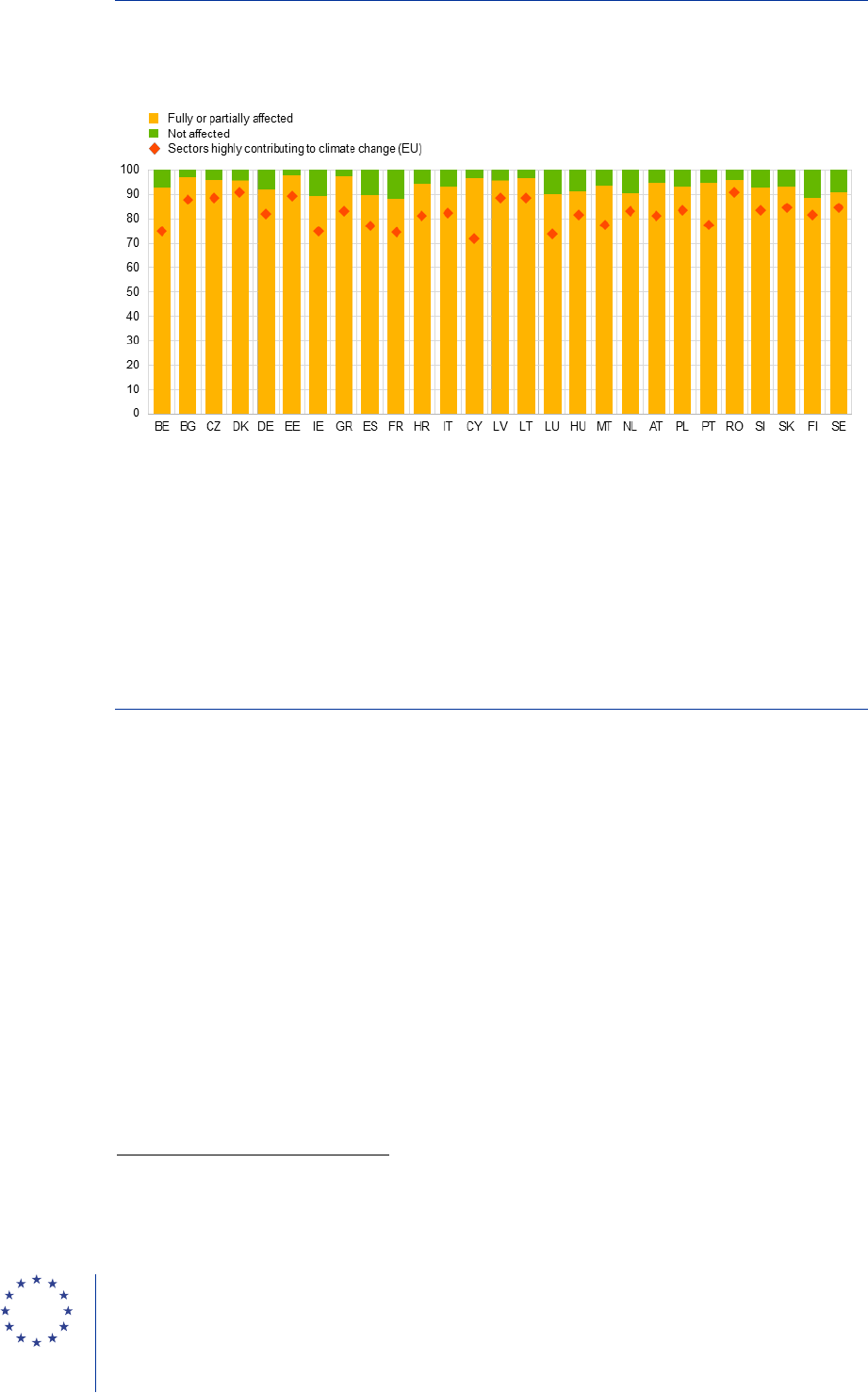

highly contributing to climate change represent around 80% of all loans to non-financial

corporations (diamonds in Chart 2). Recital 6 of Commission Delegated Regulation 2020/1818

identifies the sectors that highly contribute to climate change, as those represented by NACE codes

A to H, and L.

43

On average, they account for around 80% of the loan exposures of EU banks to

non-financial corporations. A similar classification of economic activities most affected by climate

transition risks is provided by FINEXUS: Center for Financial Networks and Sustainability, revealing

similar results.

44

,

45

From this point of view, the late and massive recognition of climate-related

changes in the asset values of non-financial corporations could have a significant impact on the

balance sheets of banks (see also Battiston et al., 2017).

46

42

At the extreme, this could lead to the valuation of the related assets and of the non-financial corporations on a gone-

concern basis.

43

See Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/1818 of 17 July 2020 supplementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1011

of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards minimum standards for EU Climate Transition

Benchmarks and EU Paris-aligned Benchmarks.

44

See Climate Policy Relevant Sectors.

45

These results depend crucially on the estimation of how climate-related risks affect each sector of activity. Different

estimations can lead, logically, to different results, particularly at national level where more granular information may be

available.

46

For further reading, see European Central Bank and European Systemic Risk Board (2023).

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Main issues identified

22

Chart 2

Loan exposures of EU banks to climate-sensitive sectors, 2022

(percentages)

Sources: ECB and ESRB Secretariat calculations.

Notes: The bars represent the share of loans to non-financial corporations affected by climate transition risks, according to the

classification by FINEXUS into sectors fully affected by climate-related risks (A – Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing, D –

Electricity, Gas, Steam and Air Conditioning Supply, H – Transportation and Storage, and L – Real Estate Activities), sectors

partially affected (B – Mining and Quarrying, C – Manufacturing, F – Construction, G – Wholesale and Retail Trade; Repair of

Motor Vehicles and Motorcycles, I – Accommodation and Food Service Activities, M – Professional, Scientific and Technical

Activities, and N – Administrative and Support Service Activities) and sectors not affected (E – Water Supply; Sewerage, Waste

Management and Remediation Activities, J – Information and Communication, K – Financial and Insurance Activities, R – Arts,

Entertainment and Recreation, and S – Other Service Activities). Sectors O – Public Administration and Defence; Compulsory

Social Security, P – Education, and Q – Human Health and Social Work Activities are considered not affected. The diamonds

represent the share of loans to non-financial corporations in the sectors highly contributing to climate change, as identified in

Commission Delegated Regulation 2020/1818. Information retrieved from the ECB’s consolidated banking data dataset for

domestic and standalone banks as well as for foreign subsidiaries and branches reporting under FINREP.

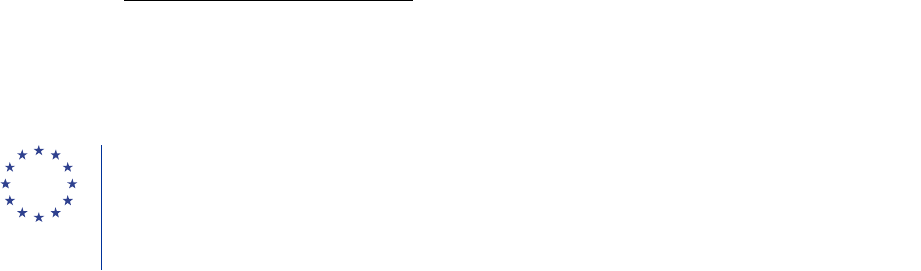

More specifically, failure to adequately consider climate-related risks in the valuation of real

estate can be a direct source of concern for banks and other financial institutions.

47

According to the EBA Risk Dashboard, EU banks had exposures towards the real estate and

construction sectors of €1.487 trillion in the second quarter of 2023, representing around 30% of

loans to non-financial corporations. Meanwhile, mortgages to households represent more than 20%

of total loans granted by banks and real estate is used as collateral in around 6% of the total loans,

thus increasing the exposure of EU banks to the real estate sector (Chart 3). The valuation of real

estate can be affected by climate-related considerations, such as the asset being located in an area

prone to flooding, a building’s energy consumption pattern or features rendering the asset

uninsurable. If not promptly addressed, these considerations could generate large losses for the

47

Although real estate is currently perceived as being particularly affected by climate-related risks, this does not prevent key

assets in other areas of activity (such as shipping or aviation) from being similarly perceived in the future.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Main issues identified

23

banking system.

48

Besides construction, real estate and mortgages, a second channel of exposure

among financial institutions relates to their direct holdings, investments or participations in

companies that hold non-financial assets potentially exposed to climate-related risks, such as

commercial real estate.

49

Chart 3

Loans related to real estate as a share of total loans of EEA banks

(percentages, EUR billions)

Sources: EBA Risk Dashboard and ESRB Secretariat calculations.

Note: Amounts refer to the second quarter of 2023, as reported to the EBA Risk Dashboard for the sample of EEA banks.

Similarly, non-financial corporations operating in certain sectors of activity may not

adequately report climate-related liabilities due, among other factors, to the prevailing

uncertainty about the future impact of climate-related risks. According to IAS 37 Provisions,

Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets, entities must recognise a provision for liabilities of

uncertain timing or amount only if an event has already occurred. Provisions must be measured at

the best estimate (including risks and uncertainties) of expenditures required to settle the present

obligation, reflecting the present value of such expenditures where the time value of money is

material. Non-financial corporations may incur sizeable liabilities as a result of compensation

sought by third parties for losses inflicted by the entity’s past polluting activity, new regulation

requiring rehabilitation of environmental damage,

50

or the liability risk resulting from non-compliance

with environmental regulation (through potential stakeholder litigation or supervisory enforcement

action). In turn, some contracts may become onerous as a result of transition risks (notably, in the

oil and gas industry), in which case the non-financial corporation is required to recognise the loss it

expects on those contracts only where an adverse climate-related event has already occurred.

48

In this regard, the modified Article 229 of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) states that “The value of the property

can exceed that average value or the value at origination, as applicable, in case of modifications made to the property that

unequivocally increase its value, such as improvements of the energy performance or improvements to the resilience,

protection and adaptation to physical risks of the building or housing unit.” (see Proposal for a Regulation of the

European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as regards requirements for credit

risk, credit valuation adjustment risk, operational risk, market risk and the output floor - Confirmation of the final

compromise text with a view to agreement).

49

See European Systemic Risk Board (2023).

50

According to IAS 37.22, such regulation should be “substantially enacted”. More generally, in order to recognise a provision

IAS 37 requires a present obligation.

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Main issues identified

24

Lack of adequate provisioning in those circumstances could cause the liabilities and costs to be

underestimated and, therefore, the company’s results to be misstated, which may ultimately raise

going-concern issues. In any case, the requirements under IAS 37 – present obligation and a

reliable estimate thereof – may limit the ability to recognise climate-related liabilities.

3.3 The incorporation of climate factors into models

Climate-related risks must be incorporated into the macroeconomic and other models used

by preparers of financial statements, including banks for the estimation of expected credit

losses.

51

When applying IFRS 9 Financial Instruments, banks (and insurance corporations) should

recognise credit losses before they are incurred, based on the possibility of a default taking place.

This requires a forward-looking perspective into the conditions and events that might affect credit

risk, their probability distribution based on default scenarios that may play out, the most relevant

loss drivers for each of those scenarios and their resulting weights, and their likely impact on the

recoverability of cash flows given the bank’s exposure.

52

Looking ahead, the models used by banks

to determine expected credit losses would need to include the likely impact of climate-related risks

as part of such forward-looking information.

53

For example, physical risks (such as those resulting

from heatwaves or wildfires) may have an impact on macroeconomic variables such as public

spending, gross domestic product or employment, or lead to large socioeconomic changes.

Physical risks can also affect the value of collateral in secured loans (for example, real estate in

areas affected by rising sea levels could experience a significant drop in value). Failing to

incorporate these factors into bank models may produce estimates of credit losses that are too

benign, as they would likely result from delayed recognition of the significant increase in credit risk

for exposures more vulnerable to climate-related risks.

54

Likewise, not considering climate-related

risk in the expected credit loss models could affect the estimation of probability of default (PD), as

well as loss given default (LGD), through overestimation of the collateral value. Box 1 discusses the

results of a recent qualitative exercise undertaken by ECB Banking Supervision on how banks are

incorporating climate-related factors into their estimations of expected credit losses.

Box 1

ECB observations on climate change in expected credit losses

55

In view of the significant impact of climate-related risks on IFRS 9 disclosures, in November

2022 the ECB ran a survey among 51 banks under its supervision. The recognition of climate-

related risks under IFRS 9 (expected credit losses and allocation of exposures to stages) is likely to

have a substantial impact, mainly on the determination of regulatory capital, management bonuses,

cost of risk, external ratings and audit assurance. The questionnaire polled banks on issues such

51

More broadly, all models used to determine the reporting entity’s expected cash flows could be affected by climate factors.

52

See Pérez Rodríguez (2021).

53

Climate-related risks should also be factored into IRB models, which not only affect the determination of capital

requirements, but are also often adapted for use in the estimation of expected credit losses.

54

The level of expected credit losses also directly impacts capital levels and therefore may have an effect on financial

stability. Furthermore, from a broader regulatory perspective, climate-related risks should also affect the computation of

risk-weighted amounts.

55

Box 1 is based on the information in McCaul and Walter (2023).

Climate-related risks and accounting April 2024

Main issues identified

25

as quantitative data for in-model adjustments and other relevant variables (including overlays),

governance and control processes in place, and collective staging. A key finding was that banks

lack the historical data on which classical expected loss provisioning models can be run.

80% of the banks responded that climate-related risks were still not considered in their

expected credit loss models (Chart A). This proportion is much larger than in the case of other

emerging risk factors such as energy supply or inflation. As for how banks incorporate climate-

related risks into expected credit loss models, 12% do so through overlays, 4% via in-model

adjustments (rating override) and 4% through the macroeconomic scenarios.

Chart A

How climate-related risks are included in expected credit loss models

(percentages)

Sources: McCaul and Walter (2023).

Within the group of banks that already incorporate climate-related risks in their expected