HAL Id: hal-01774821

https://u-paris.hal.science/hal-01774821

Submitted on 24 Apr 2018

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-

entic research documents, whether they are pub-

lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diusion de documents

scientiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Questions as indirect speech acts in surprise contexts

Agnès Celle

To cite this version:

Agnès Celle. Questions as indirect speech acts in surprise contexts. Tense, Aspect, Modality, and

Evidentiality: Crosslinguistic perspectives, John Benjamins, pp.211-236, 2018. �hal-01774821�

[Pre-final version. Please check with author before quoting. In press. Ayoun Dalila, Celle Agnès

& Lansari Laure (eds.) Tense, Aspect, Modality, and Evidentiality, Crosslinguistic perspectives,

pp. 211-236. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins [Studies in Language Companion Series

197]

Chapter 10

Questions as indirect speech acts in surprise contexts

1

Agnès Celle

Université Paris Diderot and University of Colorado

Abstract

This chapter offers an analysis of two types of interrogatives used as indirect speech acts in

surprise contexts in English – unresolvable questions and rhetorical questions. The function of

these questions is not to request information that is unknown to the speaker. It is argued that

surprise-induced unresolvable questions are expressive speech acts devoid of epistemic goals.

Surprise-induced rhetorical questions are shown not to suggest an obvious answer, but to request

a commitment update from the addressee. Adopting a schema-theoretic approach to surprise, it is

shown that unresolvable questions and rhetorical questions can express mirativity, the former at

the initial stage of the cognitive processing of unexpectedness, the latter at the last stage.

Keywords: rhetorical questions, conjectural questions, unresolvable questions, commitment,

mirativity, surprise, expressivity

1

The research leading to these results has received funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie

Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under REA grant

agreement n. PCOFUND-GA-2013-609102, through the PRESTIGE programme coordinated by Campus

France. This paper was made possible by the data annotation carried out with Hakima Benali, Anne

Jugnet, Laure Lansari and Emilie L’Hôte. I wish to thank Anne Jugnet, Laure Lansari and Tyler Peterson

for the discussions we had on questions. I am especially grateful to Anne Jugnet and Laure Lansari for

their feedback on previous drafts. I would also like to warmly thank the three anonymous reviewers for

their valuable comments and suggestions. Any remaining errors are my own.

1. Introduction

This chapter offers an analysis of interrogative structures used as indirect speech acts in surprise

contexts in English. Refining Littell et al.’s (2010) typology, I distinguish two different types of

interrogative structures: those that are mapped on the default interpretation of interrogatives, that

is, requests for information (analysed in Celle et al. forthc.), and those that are linked to other

speech acts. The latter correspond to indirect speech acts and include unresolvable questions and

rhetorical questions. These are the object of the present chapter.

In recent years, there has been a flurry of research into conjectural questions in

connection either with the conditional, the epistemic future and the subjunctive in Romance

languages (Diller 1977; Haillet 2001; Celle 2007; Rocci 2007; Dendale 2010; Bourova &

Dendale 2013; Azzopardi & Bres 2014) or with evidentials in languages that grammatically

encode evidentiality (Littell et al. 2010; San Roque et al. 2017). In Romance languages,

conjectural questions with the conditional, the epistemic future or the subjunctive are reported to

put forward an inference that the addressee is asked to evaluate. In Amerindian languages, the

insertion of an evidential into a question seems to give rise to a different meaning. Littell et al.

(2010: 92) claim that in three Amerindian languages with an evidential system, “the insertion of

a conjectural / inferential into a question creates a non-interrogative utterance, roughly

translatable using ‘I wonder’”. In this chapter, it is argued that emotive modifiers in English

cancel the interrogative force of a question in a similar way to those evidentials. Conjectural

questions in English are to be understood as expressive questions expressing wondering and

uncertainty. However, the label ‘conjectural’ may be misleading in this case, as these questions

do not form a conjecture, but rather implicate that it is impossible to resolve the question.

Therefore, I propose to label these questions unresolvable rather than conjectural.

Unresolvable questions and rhetorical questions do not constitute requests for

information. In the surprise contexts under scrutiny, unresolvable questions function as outcome-

related and speaker-oriented utterances expressing wonder and disbelief. In English, their

expressive function is marked by interjections, emotive modifiers and deictic items. Rhetorical

questions stand as argumentative tools questioning some prior surprising discourse entity or

extralinguistic event. Rhetorical questions in surprise contexts highlight the connection between

surprise and negatively-valenced emotions such as anger and disappointment.

The aim of this chapter is to determine the function of those questions that do not request

an answer in a surprise context. What do they tell us about the speaker-addressee relationship?

What is the relation between surprise and questions used as indirect speech acts? Are these

questions the linguistic expression of mirativity, and how do they relate to the cognitive

integration of unexpected new information? Section 2 presents the data. Section 3 is devoted to

surprise-induced unresolvable questions and section 4 to surprise-induced rhetorical questions.

2. The data

This study is part of a large-scale project on surprise

2

. It presents an analysis of verbal reactions

to surprising situations in the scripts of three movies (Ed Wood, War of the Worlds, Dr.

Strangelove)

3

. All surprising episodes were coded using the annotation tool Glozz

4

, based on the

same annotation scheme as Celle et al. (forthc.). The data used are enacted data. I am aware that

this type of data may bias the expression of emotions, actors being prone to overemphasise some

cues (Scherer et al. 2011: 409) as they relive an emotional experience of their own

5

. However,

enacted data allow recognizing emotions in a reliable way.

First, stage directions from the movie scripts can provide important environmental

information about the context and the experiencer’s emotional state. Second, emotions in movies

can be detected and identified through patterns of observable vocal, facial and bodily cues. On

the basis of experimentally-induced surprise reactions, Reisenzein (2000: 29) stresses that

surprise faces most frequently display only one of the facial components associated with

2

This study originates from the Emphiline project (ANR-11-EMCO-0005), “la surprise au sein de la

spontanéité des émotions: un vecteur de cognition élargie”, a project funded by the National Research

Agency from 2012 to 2015.

3

These movies provide a wealth of surprising episodes. The reasons for this choice are spelled out in more

detail in Celle et al. (forthc.).

4

Glozz is an annotation tool designed by Yann Mathet and Antoine Widlöcher. The annotation scheme

relies on units, relations and schemas. http://www.glozz.org

5

Nonetheless, on the basis of experimental studies comparing enacted and naturally-induced vocal data,

Scherer et al. (2011: 409) stress that the two procedures yield similar results, which suggests that “it may

not matter very much whether emotional expressions are enacted or experimentally induced, at least for

some major emotions”.

surprise: eyebrow raising, eye widening, or mouth opening, while two- or three-component

displays are less frequent. He further points out that this finding is in keeping with Carroll and

Russell’s (1997) enacted data based on the facial displays of surprise shown by movie actors.

Even if the present chapter does not aim to analyze intonation and gestures, those parameters

were taken into account in our annotation scheme and facilitated emotion recognition. The

semasiological perspective adopted is thus combined with an onomasiological approach, that is,

only interrogatives occurring in surprise contexts were considered.

Interrogative clauses used as indirect speech acts are questions that do not request an

answer from the addressee, although they may call for some response from the addressee. They

amount to 13% of all interrogatives in our sample (26 utterances out of a total of 146

interrogatives). These interrogative clauses are subdivided into rhetorical questions (n = 12),

unresolvable questions (n = 5), and clarification requests (n = 9)

6

. Like the interrogative clauses

used as direct speech acts examined in Celle et al. (forthc.), the interrogative clauses found in our

sample are triggered by some surprising event

7

. Unlike their counterparts used as direct speech

acts, however, they have no force of inquiry. The connection between surprise and interrogative

clauses used as indirect speech acts needs to be accounted for; so does the nature of the speaker-

addressee relationship when no answer is requested. I first examine unresolvable questions

before moving on to rhetorical questions.

3. Unresolvable questions

Unresolvable questions are the least frequent category of surprise-induced questions in our

sample (n= 5). This category is based on the conjectural question type put forward by Littell et

al. (2010) to account for the wonder effect produced by the insertion of a conjectural / inferential

evidential into a question in three Amerindian languages. Littell et al. maintain that conjectural

questions are wonder-like statements, although formally, they are wh-interrogatives. The claim

6

Clarification requests straddle the border between direct and indirect speech acts. As shown by Celle et

al. (forthc.), clarification requests may be used as indirect speech acts in a purely expressive way.

7

Embedded interrogatives are left aside in this paper. For a comparison of the uses of root interrogatives

and embedded interrogatives, see Celle (2009).

made in this paper is that a similar wonder effect is produced by the insertion of emotive

modifiers into a question in English. However, strictly speaking, these questions do not express a

conjecture in the sense that they cannot be rephrased using “I surmise / I presume“ + content

clause

8

. It is the proposition as a whole that is a matter of conjecture. In and of itself, this

question type reflects the speaker’s ignorance rather than their conjecture. Therefore, I propose

to dub these questions unresolvable rather than conjectural. Emotive modifiers indicate that the

situation is appraised as violating the speaker’s expectations to such an extent that the question-

answer presupposition is cancelled.

In the surprise contexts that were examined for the present study, unresolvable questions

may contain interjections (such as ‘shit’, ‘gosh’), emotive modifiers (such as ‘on earth’ or ‘the

hell’)

9

or deictics, that is, items that mark the speaker’s emotional involvement and context-

boundedness (see Ameka 1992: 108). Some of these items are swearwords (‘gosh’, ‘shit’, ‘the

hell’) used cathartically (see Pinker 2007), that is, they serve an intra-individual function by

reducing the stress associated with the utterance situation once it has been appraised as

discrepant. Both interjections and emotive modifiers take the utterance situation as the source of

surprise. As noted by Vingerhoets, (2013: 290), “cathartic swearing is regarded as an

adaptation,

10

especially meant to communicate that the situation we are confronted with deeply

affects us, as evidenced by the display of strong emotions”.

8

In French, the inferential conditional used in an interrogative clause produces a conjectural question,

and not an unresolved question: Or cet enfant venait d’être volé par un inconnu. Quel pouvait être cet

inconnu ? Serait-ce Jean Valjean ?[The child had just been stolen by an unknown man. Who could that

unknown man be? Could it be Jean Valjean?] (Hugo, 1862, Frantext). As stated by Dendale (2010: 297;

302), the “interlocutive function” of the question is affected by the conditional. However, the reason for

the weakening of the interrogative force is that the speaker believes the proposition to be true. The

conjectural question may be considered a mitigated assertion that can be rephrased as “I surmise that p”

(Je suppose que c’est Jean Valjean). As shown by Diller (1977: 3-4), the conditional conveys a

presupposition of evidence that is superimposed on the question, which reduces its interrogative force.

She argues that a conjectural question in the conditional asserts a presupposition. I claim that a

conjectural question seeks the addressee’s commitment (Celle 2007). By contrast, expressives in

unresolvable questions are triggered by defective evidence. They implicate that no value can instantiate

the question variable, which precludes assertion. This can be paraphrased as ”I don’t know if p ; I don’t

know where / what / how …”.

9

The distinction between interjections and emotive modifiers is borrowed from Huddleston & Pullum

(2002: 916).

10

My emphasis. The adaptation marked by swearing may be regarded as the verbal expression of the

cognitive and emotional adaptation to unexpected events that underlies surprise (see Darwin 1872/ 1965).

Adjustment to direct evidence is a feature shared by questions with emotive modifiers in

English and conjectural questions in the languages that have evidentials or inferential

conditionals. It gives credence to the claim that unresolvable questions are a cross-linguistic

phenomenon that can be extended to English. Indeed, emotive modifiers point to defective

evidence about the potential answers to the question, so that the addressee cannot be expected to

provide an answer.

The fact that these highly emotional questions are systematically content questions

suggests that a correlation can be established between speaker perspective and wh-questions (as

shown by Celle & al. (forthc.) in the case of interrogatives used as direct speech acts, and by San

Roque et al. (2017) in the case of evidential questions). This correlation is all the more striking

as the most frequent questions in standard communication contexts in English are polar questions

(see Stivers 2010; Siemund 2017). This suggests that the more emotional a question is, the more

open-ended the set of answers will be. Unresolvable questions used in surprise contexts are about

a salient open proposition. The clash between the speaker’s expectations and the incongruous

character of the situation makes it impossible for the speaker to assign a value to the question

variable and to expect the addressee to be able to do so.

In Littell et al’s (2010) typology, conjectural questions differ from rhetorical questions in

that the speaker does not know the answer; they also differ from ordinary questions in so far as

they do not require an answer from an addressee. This holds true for unresolvable questions in

English:

(1) Ed : Whoa, look at this camel, this is a real camel, Gosh, where’d they get a real

camel?

(2) Bela: Oh, there's my bus. [he checks his pockets] Shit, where's my transfer?!

Ed: Don't you have a car?

(3) EXECUTIVE 1 What the hell is this?!

EXECUTIVE 2 Is this an actual movie?!

These questions can be rephrased as follows:

I don’t know / wonder where they got a real camel.

where my transfer is.

what this is.

The source of wondering is the unexpected presence, absence or location of some element in the

utterance situation. In other words, the cause of surprise is an extralinguistic event that violates

the speaker’s expectations. It is some new environmental information (see Peterson 2017) that

may be surprising to both speaker and addressee. As such, it constitutes defective evidence, to

the point that the experiencer cannot make inferences about the situation (Stein & Hernandez

2007: 302). The experiencer is forced to revise his / her previously held beliefs. In (1), there is a

real camel on stage although the speaker assumes there should not be one; in (2), the transfer is

not in the speaker’s pocket although it should be there; in (3), the properties of the movie defy

the speaker’s ability to characterize it. At the same time, the specific contribution of the

interjection or the emotive modifier is that evidence is so defective that the addressee is not

expected to know the answer.

These questions may even be self-addressed as in (1), where there is no addressee. In (2)

and (3), no answer is provided by the addressee who responds by asking a biased question or a

rhetorical question, and the interchange is perfectly felicitous. In (3), the follow up polar

question restricts the set of possible values for the question variable and specifies the nature and

quality of the entity that both speaker and addressee find surprising.

Pragmatically, unresolvable questions are speaker-oriented, like exclamative utterances.

Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 916) stress that emotive modifiers “express surprise or

bafflement, and hence suggest that the speaker does not know the answer to the question. They

tend to emphasise the open-endedness of the set of possible values for the question variable.”

Noteworthy is the fact that they may be followed by a question mark as well as an exclamation

mark. However, these questions have the syntax and the semantics of interrogatives.

Syntactically, they require subject auxiliary inversion. Semantically, they are concerned

with the identification and the appraisal of an incongruous situation

11

, not with degree. Unlike

most exclamatives, unresolvable questions carry no explicit “scalar implicature” (Michaelis and

Lambrecht, 1996: 378)

12

. However, they do imply an implicit scale by suggesting that the actual

state of affairs violates the speaker’s expectations or norms in an extreme way.

11

The concept of “incongruity judgement” was originally coined by Kay & Fillmore (1999).

12

A parallel may be drawn here between unresolvable questions and the WXDY construction as defined

by Kay and Fillmore (1999: 25-26). However, in the case of unresolvable questions, mirative meaning is

related to their deictic nature. As shown by Kay and Fillmore, WXDY constructions can express a sense

of incongruity independently of the situation of utterance as they can be embedded. See also Celle &

Unresolvable questions containing interjections may be differentiated from those

containing emotive modifiers for two reasons. First, the valence associated with interjections

may be either positive (1) or negative (2), while emotive modifiers tend to be associated with a

negative valence (3). Second, emotive modifiers convey a stronger expressive meaning than

interjections, which has implications on the function of the speech act. Unresolvable questions

containing interjections allow continuation with an informative answer, although they do not

request an answer:

(1’) A - Whoa, look at this camel, this is a real camel, Gosh, where’d they get a real

camel?

B - In the Sahara.

(2’) A - Oh, there's my bus. Shit, where's my transfer?!

B – You must have left it at home.

As stated by Ameka (1992: 107) interjections “encode speaker attitudes and communicative

intentions and are context-bound”. They express the speaker’s emotional reaction to some

unexpected event: the presence of a real camel in (1), the absence of the transfer in (2). The

transfer is not where it is expected to be, the real camel is unexpected in this setting, hence the

unresolvable questions about the origin of the camel in (1) and about the location of the transfer

in (2). The answer may well increase the speaker’s knowledge by assigning a value to the place

variable in (1’) and (2’). However, the aim of the question is not to increase the speaker’s

knowledge, but to express the emotional reaction of the speaker faced with an unexpected

discrepant situation. Whatever the answer, it does not eliminate the sense of surprise.

Emotive modifiers provide questions with a strong expressive force, which overrides

referential meaning. ‘The hell’ systematically follows the wh-word and the sequence “wh-word

the hell” is a semi-fixed phrase. In (3), the speaker’s question is triggered by visually perceived

incongruous evidence. As the speaker is witnessing the situation, the addressee’s answer is

redundant in the sense that it does not increase the speaker’s knowledge:

(3’) ‘What the hell is this?!’

‘This is an actual movie.’

Lansari (2015) on aller + infinitive in one of its uses. This calls for further research into the connection

between mirative constructions (possibly unrelated to the speaker’s here and now) and mirative utterances

(deictically related to the speaker).

Paradoxically, this referential answer is also insufficient because it fails to account for the

incongruous character of the state of affairs. Providing a value for the variable is not enough to

account for the incongruity of the state of affairs. The unresolvable question is not about the

identification of the situation the speaker is witnessing. It conveys a negative assessment of the

film movie that is being watched because the movie does not meet the standards of an actual

movie. The answer can eliminate neither the sense of incongruity nor the negative assessment.

Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 916) rightly note that ‘which’ cannot substitute for ‘what’

when a what-question contains an emotive modifier. According to them, the open-endedness of

the set of possible values implied by emotive modifiers accounts for that restriction: “as a result,

they are hardly compatible with which, for this involves selection from an identifiable set”. This

reasoning can be carried one step further. I argue that these questions are not concerned with the

identification of a referential entity. The emotive modifier the hell cancels the question-answer

presupposition by suggesting that whatever the answer, the situation violates the speaker’s

expectations to such an extent that their state of surprise and negative assessment cannot be

altered

13

. Given the extreme character of the situation, any informative answer is epistemically

pointless. This type of question constitutes an expressive speech act devoid of any epistemic

goals (see Zaefferer 2001: 224).

Interjections and emotive modifiers impart a mirative meaning to unresolvable questions,

although mirativity is not encoded morphosyntactically in English. As stressed by DeLancey

(2001: 377-378), mirativity is a “covert semantic category” in English, as opposed to other

languages. However, interjections and emotive modifiers do encode the speaker’s surprise and

relate it to new environmental information. Strikingly, all the unresolvable questions in our

sample are induced by new environmental information and not by a surprising discourse entity.

13

In the surprise contexts studied in this paper, the wh-word-‘the-hell’ phrase indicates that the cause of

surprise is the utterance situation. In such contexts, I argue that the phrase cancels the question-answer

presupposition. However, the wh-word-the-hell phrase may be used in requests for information that

simultaneously carry an instruction of unresolvedness, especially when reference is made to a past event.

In the following example borrowed from den Dikken & Giannakidou (2002: 32), the interrogative is an

information question about the identity of the buyer: ‘Who the hell bought that book?’ As stated by den

Dikken and Giannakidou (2002: 32), the wh-word-‘the-hell’ phrase conveys the presupposition that

‘Nobody was supposed to buy the book’. This results from the instruction of unresolvedness (i.e. the

speaker's failed attempt to resolve the question), which is nonetheless compatible with a genuine

information question about the identity of the buyer as the event is presumed to have occurred in the past.

By contrast, questions used as direct speech acts in surprise contexts (i.e. clarification requests,

ordinary questions and inferential questions) are mainly induced by a surprising discourse entity

(see Celle & al. forthc.) and therefore do not qualify as mirative utterances (see Peterson 2017:

68).

The incompatibility of emotive modifiers (such as ‘the hell’, ‘on earth’) with echo

questions Fillmore (1985: 82) and with which-questions observed by Huddleston & Pullum

(2002: 916) and Pesetsky (1987: 111) substantiates this claim by suggesting that the surprising

element cannot be traced back to the previous discourse. To quote Pesetsky (1987: 111), ‘the hell

forces “a non-discourse-linked reading”, while “which-phrases are discourse-linked”. It is the

context-boundedness of emotive modifiers that allows for the indexical mirative meaning of

unresolvable questions.

The mirative meaning of this type of question can be probed using the undeniability test

(Rett & Murray 2013: 455; Celle & al. 2017: 220):

(3’’) A. ‘What the hell is this?!’

B. # ‘You are not surprised’.

The sense of surprise cannot be denied, which reveals that this utterance is an expressive speech

act (see Potts 2005: 157). As such, the mirative speech act can only reflect the speaker’s

emotional state, and the addressee cannot deny that emotional state.

Interestingly, Alcázar (2017: 37) points out that in Basque, the mirative particle ote often

collocates with swearwords equivalent to ‘the hell’ in questions of the type ‘Can’t-find-the-

value-of-x’. There seems to be typological evidence that the use of emotive modifiers in

unresolvable questions pertains to mirativity. Like evidentials in some languages, emotive

modifiers may shift the interpretation of questions, which take on an ignorance meaning.

14

This

shows that they have not only an intensifying or emphatic function in questions (Hoeksema &

Nicoli 2008). They also have an illocutionary effect on interrogatives.

4. Surprise-induced rhetorical questions

14

However, more research is needed to elucidate the relation between indexicals, evidentials and emotive

modifiers. Some scholars (see for example Korotkova 2016: 224-226) argue that evidentials are

addressee-oriented in questions, in contrast to indexicals which remain speaker-oriented.

4.1. Expectation violation

Formally, rhetorical questions resemble questions used as direct speech acts. Surprise-induced

rhetorical questions can enter into the same syntactic patterns as direct questions, except the

declarative pattern. Rhetorical questions have an interrogative syntax in a more systematic way

than ordinary questions. Wh-questions with subject-auxiliary inversion account for half of all the

interrogative clauses used as indirect speech acts in my sample. The different types of rhetorical

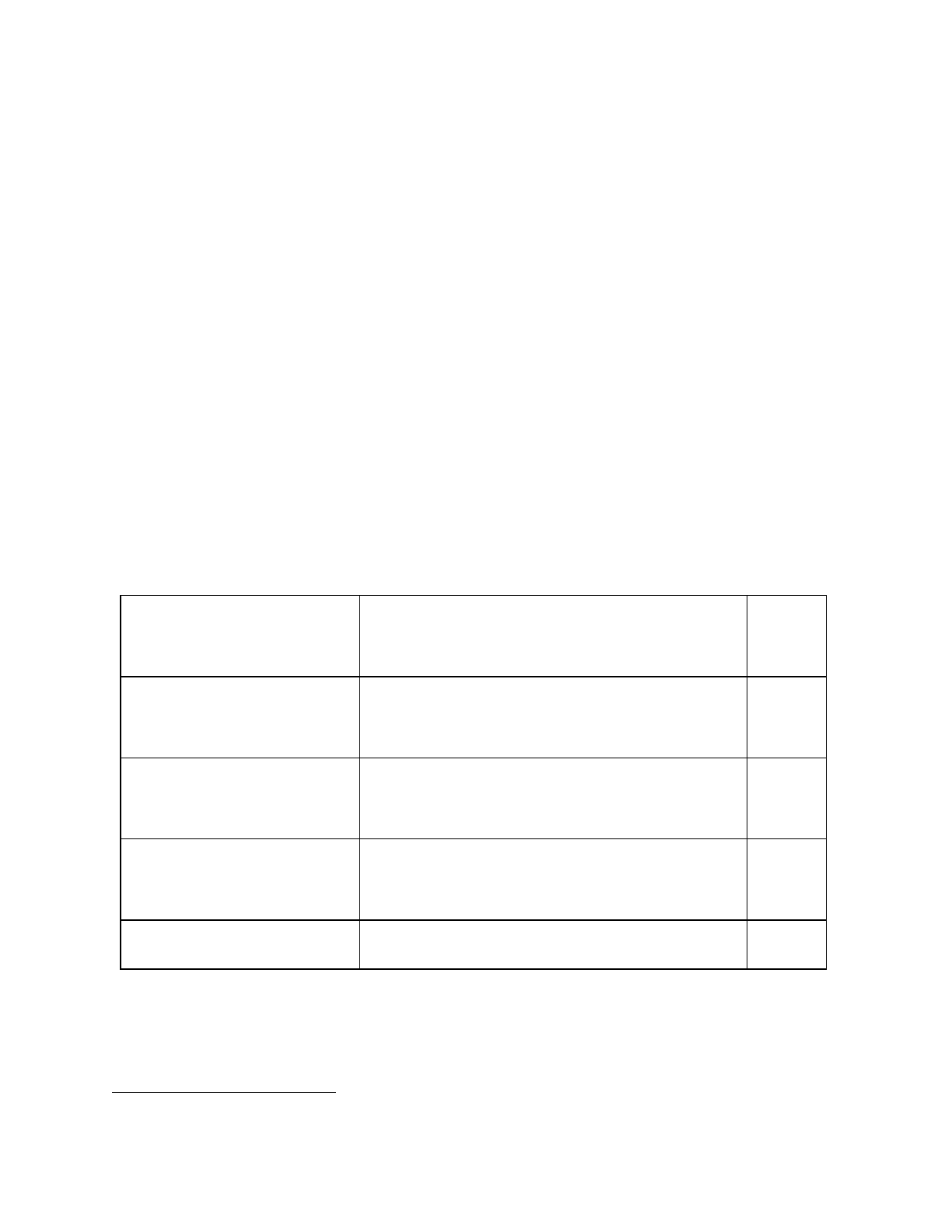

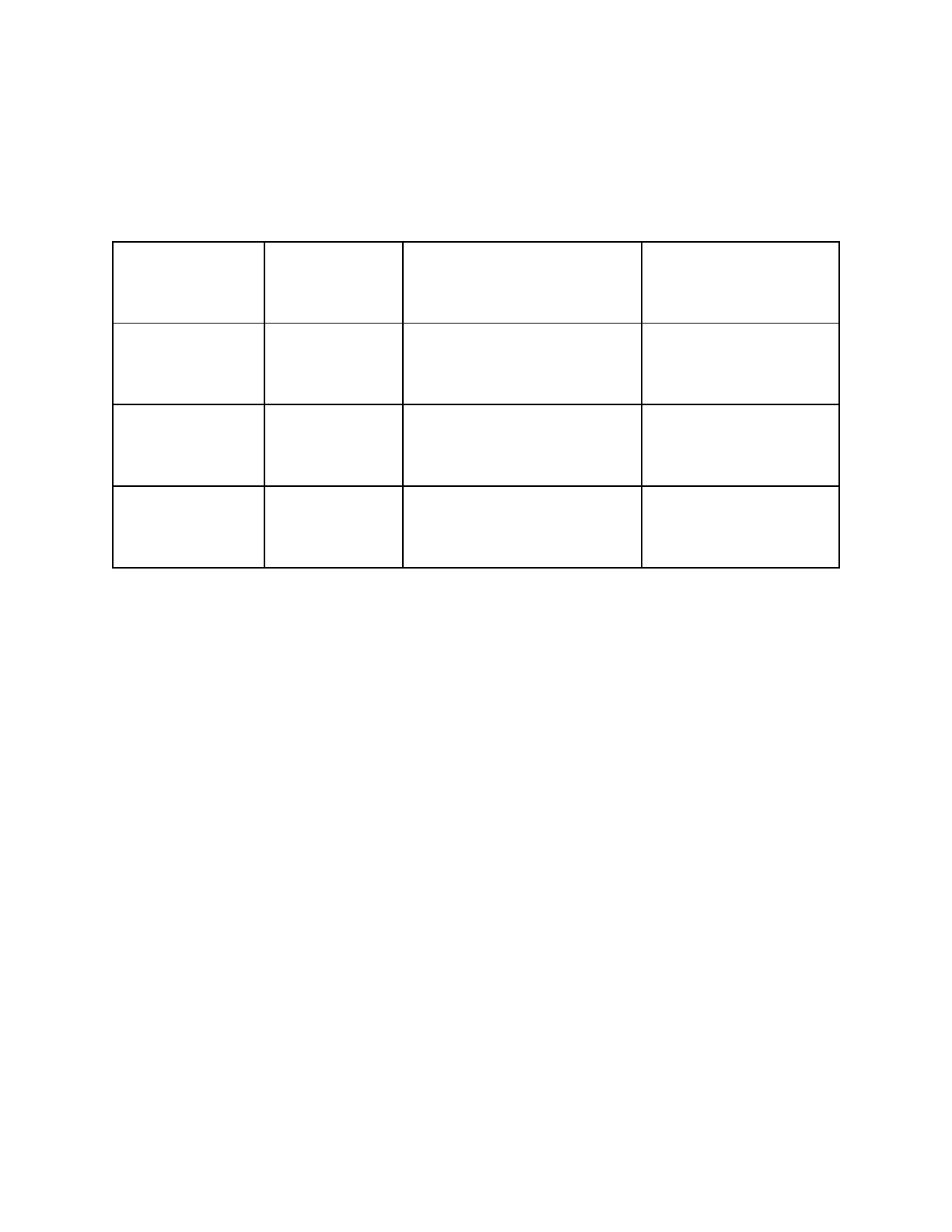

questions are classified in Table 1.

[Insert Table 1 here]

Table 1: Types of rhetorical questions

Wh-question: Wh-word +

subject-auxiliary inversion

What kind of sick mind would operate like that?

5

Yes/no question

Can you imagine what that guy would be like in

a movie?

4

Reprise fragment

15

Stronger? You see! You see!! You stupid minds!

Stupid!

1

Wh- question: clause

fragment

And what about this so-called “Barbara”

character? It’s obviously ME!

1

Reprise sluice

Since when?

1

In total, wh-questions (including a reprise sluice and a verbless sentence) are found in 8 out of 12

rhetorical questions. This confirms the correlation established above as well as in Celle et al.

15

This term is borrowed from Ginzburg (2012).

(forthc.) between surprise and wh-questions, that is, questions that denote a set of possible

answers. Wh-words include ‘what’ (n = 3), ‘when’ (n = 2), ‘how’ (n = 3). ‘How’-questions are

always associated with a modal auxiliary in their rhetorical reading. Among the elements that

facilitate a rhetorical reading are also deictic items (‘like that’) and degree words (‘so casual’).

Semantically, rhetorical questions define either a closed set of possible answers or an

open set of possible answers, the latter being the most frequent case in my sample.

Informationally, rhetorical questions are complete utterances, as opposed to ordinary questions.

Pragmatically, they express a biased position by pointing towards an obvious answer (Rohde

2006:149). As pointed out by Caponigro and Sprouse (2007: 131), “[r]hetorical questions are not

asked to trigger an increase in the amount of mutual knowledge”, nor do they assert anything

new. This raises two questions that are addressed below. First, how can rhetorical questions

qualify as questions? Second, why are rhetorical questions used to express surprise? Such

expressions reveal an epistemic asymmetry, the speaker’s expectations conflicting with the

addressee’s beliefs or with the state of affairs. In her analysis of responses to rhetorical

questions, Rohde (2006: 142) notes that rhetorical questions “generate very little surprise”:

“[T]he case of complete lack of surprise corresponds to rhetorical questions because the answer

is predictable to both the Speaker and the Addressee. The answer is so unsurprising that it need

not be uttered at all.” (ibid: 147).

My analysis of responses to rhetorical questions yields similar results: the answer to the

rhetorical questions found in surprise contexts need not be uttered

16

. However, it may not be

because the answer is unsurprising. Under Rohde’s analysis (2006: 152), the fact that rhetorical

questions generate little surprise is “evidence of their uninformativity”. Adopting Gunlogson’s

(2001) Common Ground theoretical framework, Rohde (2006: 152) views this uninformativity as

indicative of the fact that rhetorical questions “require no update to participants' commitment

sets”. This view is challenged in the present chapter. It is also argued that informativity and

update of the participants’ commitment sets should be distinguished. In surprise-generated

rhetorical questions, no informative answer is requested, but rhetorical questions are uttered in

reaction to some unexpected linguistic information or incongruous situation and involve a two-

16

Rohde (2006) uses naturally-occurring language data drawn from the Switchboard corpus, a corpus of

telephone speech. Her approach is purely semasiological - i.e. her analysis is not focused on rhetorical

questions occurring in surprise contexts.

fold update. First, they signal the speaker’s attempt to cognitively integrate unexpected new

information. Second, they request a commitment update on the part of the addressee. With

respect to surprise, Rohde only examines responses to rhetorical questions without considering

how these questions may lend themselves to the expression of surprise. I contend that rhetorical

questions may be used to express surprise precisely because the nature of the speech act they

convey allows for the expression of conflicting views in a questioning process whereby the

addressee is asked to update his / her commitment.

My claim is that this pragmatic commitment update process is highly congruent with the

appraisal process that underlies the surprise reaction on the psychological level. Within a

schema-theoretic framework, Meyer et al. (1997: 253) characterize the surprise-induced

appraisal process as follows:

[S]urprise-eliciting events initiate a series of processes that begin with the appraisal of a

cognized event as exceeding some threshold value of schema-discrepancy (or

unexpectedness), continue with the occurrence of a surprise experience and,

simultaneously, the interruption of ongoing information processing and reallocation of

processing resources to (i.e. the focusing of attention on) the schema-discrepant event,

and culminate in an analysis and evaluation of this event plus – if deemed necessary – an

updating, extension, or revision of the relevant schema.

The questioning process encoded by rhetorical questions necessarily requests a commitment

update from the addressee. Furthermore, surprise-induced rhetorical questions appear to be much

more complex emotionally than surprise-induced ordinary questions. Surprise may be tinged

with anger in rhetorical questions that are typically asked to express disbelief and disagreement.

In that case, expectation violation is coupled with the violation of standards and the thwarting of

the experiencer’s goals, which correspond to the ingredients of anger as defined by Ortony and

al. (1988: 152-153).

4.2. Informative answers

Rhetorical questions are generally said to be semantically equivalent to statements because they

contain the answer to the question they ask and do not request an answer from the addressee. The

view upheld in the present chapter is that rhetorical questions necessitate a pragmatic account.

Even when the rhetorical intent is obvious from the pragmatic context and the semantic

construction, the addressee may fail or deliberately refuse to recognize it. In that case, an

informative answer may be provided:

(4) Reverend Lemon: Mr. Wood? What do you think you're doing?!

Ed: I'm directing.

Reynolds: Not like THAT, you're not!

(5) Rachel : I'm allergic to peanut butter.

Ray : (laughs) Since when?

Rachel : (with a snotty look) Birth!

These questions fail the tests designed by Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) to reveal information-

seeking questions

17

:

(4’) # I’m really curious: What do you think you're doing?!

# I really don’t know: What do you think you’re doing?!

(5’) # I’m really curious: Since when (have you been allergic to peanut butter)?

# I really don’t know: Since when (have you been allergic to peanut butter)?

In addition to these tests, rhetorical meaning is also revealed by certain interrogative phrases.

When as a complement of the preposition since is less likely to request an informative answer

that selects a temporal starting point. It suggests a sudden start that may not be relevant to some

states, such as being allergic

18

. As noted by Huddleston & Pullum (2002: 905), “‘since when’ is

often used sarcastically, with cancellation of the presupposition”. In the following example,

‘since when’ points to a rhetorical reading in a similar way:

(6) Robbie: I don’t have a license.

Ray: Since when has that stopped you?

The ‘since when’-question is not about the starting point of the stopping process but cancels the

question-answer presupposition ‘That has stopped you for some time’. The rhetorical question

implies ‘That has never stopped you’. Consequently, Robbie’s statement ‘I don’t have a license’

loses its argumentative force as a justification for not driving.

Contrast with a ‘how long’-question:

(7) A - I’m allergic to peanut butter.

17

Except in sarcastic contexts where they are felicitous, as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer.

18

As rightly pointed out by an anonymous reviewer.

B - How long have you been allergic to peanut butter?

This question is accompanied by a question-answer presupposition (‘you have been allergic to

peanut butter for some time’) and seeks to assign a value to a variable in an open proposition

(‘you have been allergic to peanut butter since X’).

Although the questions in (4) and (5) are unequivocally rhetorical, they are followed by

an informative answer. Such answers are not requested. However, they are perfectly compatible

with rhetorical questions syntactically and conversationally because rhetorical questions are

questions, not assertive statements. They are made possible by the semantic nature of these

questions, which denote a set of potential answers (‘playing’, ‘working’, ‘directing’, etc. in (4),

‘since birth’, ‘since 1960’, ‘since the war’, etc. in (5)). Nonetheless, such answers refute the

rhetorical scenario on the pragmatic level and express disagreement. Instead of acknowledging

the rhetorical intent whereby the speaker points to some answer supposedly obvious to both

speaker and addressee (i.e. ‘whatever you think you’re doing is wrong, you have never been

allergic to peanut butter’), the addressee may well choose to assign a value to the variable as if

the question were information-seeking.

According to Rohde (2006: 161), rhetorical questions are understood as such by virtue of

their properties of “answer obviousness” and “similarity”, that is, the answer to a rhetorical

question is obvious to speaker and addressee and they supposedly both share a commitment to an

answer similar in nature. However, an unco-operative addressee may reject or ignore the

rhetorical effect imposed by the speaker even if it is recognized as such. It is noteworthy that

informative answers are found in the case of second-person utterances – or at least in questions

involving the second person as in the reprise sluice in (5). These rhetorical questions are indirect

speech acts that challenge either what the addressee is doing (as in (4)), or what the addressee

has just said (as in (5)) because speaker and addressee do not share the same standards or the

same beliefs. The sense of absurdity conveyed by the rhetorical questions may not be shared by

the addressee. Providing an informative answer amounts to assigning a value to a variable as in

the case of an ordinary question. In this way, the addressee avoids committing to the proposition

that is indirectly asserted by the rhetorical question (‘You are messing up’ in (4), ‘You have

never been allergic to peanut butter’ in (5)). The rhetorical question then fails to update the

addressee’s commitment.

4.4. The surprise-induced rhetorical scenario

Rhetorical questions may be followed by an informative answer, although they do not invite such

an answer. More often than not, they are followed by a response. Each case is examined in turn.

(8) Dolores: Ugh! How can you act so casual, when you're dressed like that?!

Ed: It makes me comfortable.

The answer can be construed as the causal explanation for acting so casually. It indicates that the

question is taken to carry a presupposition (‘you act very casually when you’re dressed like that’)

while the implied assertive statement, that is, the implicit evaluative judgment implied by the

question (‘you shouldn’t act so casual when you’re dressed like that’), is ignored, which foils the

rhetorical strategy. The rhetorical strategy fails in a similar way in the following constructed

examples:

(9) A - Ugh! How can you act so casual, when you're dressed like that?!

B – Thanks to my talent.

(10) A - How can you just walk around like that, in front of all these people?

B – With a walking stick.

(11) A - Goldie, how many times have I told you guys that I don't want no horsin'

around on the airplane?

B – Just once.

These answers signal that the addressee deliberately ignores the rhetorical scenario imposed by

the speaker. By contrast, responses do not attempt to undermine the rhetorical strategy, but take

disagreement for granted:

(12) Dolores: How can you just walk around like that, in front of all these people?

Ed: Hon', nobody's bothered but you.

(13) Kong: Goldie, how many times have I told you guys that I don't want no horsin'

around on the airplane?

Goldie: I'm not horsin' around, sir, that's how it decodes.

In (12) and (13), the responses signal the addressee’s disagreement with the evaluative

judgments expressed in the rhetorical questions. As such, these rhetorical questions force the

addressee to accept the implied assertive statement, and do not request a response. First, I define

the nature of the discrepancy conveyed by rhetorical questions before taking up the issue of

addressee commitment.

Surprise-induced rhetorical questions express a conflict between the speaker’s epistemic

domain and the actual state of affairs: in (13), the rhetorical question implies an indirect assertive

statement: ‘I have told you so many times that I don’t want no horsin’ around on the airplane’.

The source of the speaker’s surprise is the soldier’s preceding answer, which confirms surprising

information. This answer is mistakenly construed as a joke, i.e. as an act of disobedience. The

rhetorical question indicates that the speaker is epistemically unprepared to face a totally

unexpected turn of events and is therefore unable to behaviorally adapt to it. Discrepancy arises

from the speaker’s failure to correctly interpret an unexpected answer. Some fact is directly

perceived but misinterpreted.

When rhetorical questions contain modal auxiliaries, they typically express a conflict

between realis and irrealis:

(14) What kind of sick mind would operate like that?

The modal ‘would’ occurs with question-answer presupposition cancellation, that is, the

presupposition that some value can be supplied for the subject variable is cancelled by

modality.

19

The rhetorical question implies an indirect assertive statement, namely that ‘no sound

mind would operate like that’. In reaction to an actual situation for which the speaker is

epistemically and morally unprepared, a hypothetical stance is adopted that strips the surprising

situation of its realis quality. Surprise is related to the irrealis domain (see Akatsuka 1985). This

sense of reality denial is particularly striking with how-rhetorical questions, which always

contain the modal auxiliary can in my sample (as in (8) or (12)).

As noted by Desmets and Gautier (2009 : 109), comment ‘how’-rhetorical questions in

French (such as Comment peux-tu déambuler de cette façon?) contain two contradictory pieces

of information (tu déambules de cette façon and tu ne peux pas déambuler de cette façon). The

same analysis holds for how-rhetorical questions in English. Indeed, (8) and (12) carry a

presupposition that p (‘you are walking around like that, with such accessories’ in (12), and ‘you

are acting so casual’ in (8)) that conflicts with the negative comment implied by the rhetorical

19

For a detailed account of would in questions, see Celle (in press) and Celle & Lansari (2014) and

(2016).

questions (‘you can’t walk around like that, in front all these people’ in (12) and ‘you can’t act so

casual, when you’re dressed like that’ in (8)).

Counterfactual evidence runs counter to the assertion of p. It is supplied by a variety of

markers, such as a temporal when-clause, a degree modifier (‘so casual’), deictic items (‘like

that’), and a spatial PP (‘in front of’ …). These markers all signal a violation of the speaker’s

expectations and are conducive to the indirect assertion of non (modality) p, although p is

presupposed

20

. This discrepancy accounts for the mirative meaning of these rhetorical questions.

3.5. Addressee commitment

In surprise contexts, rhetorical questions may be considered mirative utterances

21

not only

because they express surprise, but also because the discrepancy they convey triggers a specific

stance on the part of the speaker. Modalised rhetorical questions deny reality either by cancelling

the question-answer presupposition

22

or by relying on counterfactual evidence

23

. The speaker

directly perceives some event, which should lead to the assertion of p, the status of p being in no

doubt. And yet, the speaker does not commit to the truth of p, because p runs counter to her

expectations. The function of rhetorical questions is then to question the grounds that made p

possible. In a rhetorical question, the speaker selects an answer and requests the addressee to

commit to the truth of that proposition

24

. Rhetorical questions are biased because they do not

20

This notation is borrowed from Desmets and Gautier (2009). They argue that comment-rhetorical

questions in French conflate a question about the modal operator (pouvoir) of the proposition and an

assertion that negates both the modal operator and the proposition. How-rhetorical questions in English

with the modal auxiliary ‘can’ behave in a similar way.

21

Mirativity is defined by several authors (among others, Guentchéva (2017), Peterson (2017)) as

resulting from a discrepancy between what is observed and what is expected.

22

On cancellation of question-answer presupposition, see Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 900-901).

23

My translation of “indice contrefactuel”, a concept borrowed from Desmets and Gautier (2009: 111).

24

I agree with Desmets & Gautier (2009) and Beyssade & Marandin (2009) that the speaker requests the

addressee’s commitment to a proposition in rhetorical questions. However, rhetorical questions do not

necessarily request a verbal response, let alone an answer. They seek the addressee’s alignment, but it is

not clear whether the addressee will actually commit to the proposition suggested by the speaker. If

rhetorical questions are not generated by surprise, anger or disagreement, the assertion they imply is

uncontroversial and the answer to the question is obvious. The absence of an answer from the addressee

may then be interpreted as tacit agreement. In emotion-induced rhetorical questions, however, a

commitment update on the part of the addressee is requested. In half of the examples of my sample,

leave any choice to the addressee with respect to the selection of a variable. However, they are

questions in the sense that they request the addressee’s commitment to a proposition. They can

be preceded by the discourse marker tell me, which, as shown by Reese (2007: 51) co-occurs

with questions that request a response, but not with assertions. Asked to commit to a proposition

that stands in contrast to the state of affairs or to her beliefs, the addressee may not respond:

(15) Ed: This is my way of telling you –

Dolores: [furious] What, by putting it in a fuckin' script, for everyone to see?!

What kind of sick mind would operate like that?

[Ed is terribly hurt. Dolores shakes that script.]

Dolores: And what about this so-called "Barbara" character? It's obviously ME!

I'm so embarrassed! This is our life!

The rhetorical question allows the speaker to express disapproval without committing to the

proposition ‘You are a sick mind’. The addressee is asked to commit to the proposition ‘No

sound mind would operate like that’. This indirect insult may reach its goal emotionally, as

specified in the stage direction (‘Ed is terribly hurt’). From an interactional perspective, however,

it is a dead end.

25

Unless an unlikely response such as ‘You are right’ or ‘I know’ is uttered, no

commitment update is possible on the part of the addressee.

In (8) and (12) a response is provided by the addressee, but it does not update the

common ground in the way expected by the speaker: what is presented as counterfactual

evidence according to the speaker’s standards is said to be normal behavior in the addressee’s

response. As a result, the contradiction conveyed by the rhetorical question is cancelled and the

speaker is forced to accept p, even if the rhetorical question requests the addressee to commit to

non (modality) p. In (13), the addressee’s response forces the speaker to revise his appraisal of

the situation.

rhetorical questions are not followed by a response or an answer. In the absence of any explicit verbal

reaction from the addressee, it is difficult to determine whether the speaker and addressee’s common

ground is eventually updated.

25

Although surprise-induced rhetorical questions may take different forms and do not as such constitute a

construction, a parallel may be drawn here with the Split Interrogative construction analysed by Michaelis

& Feng (2015). The conversational dead end is typical of what Michaelis & Feng (2015: 149) call

sarcastic syntax. Under their analysis, ironic utterances are “counterfeit speech acts” that “do not advance

the conversation” because their function is “disruptive”.

The analysis of emotion-induced rhetorical questions shows that the response to a

rhetorical question is not obvious to both speaker and addressee when they have different

expectations. Contra Rohde (2006: 149-150), I argue that the addressee may be committed to a

proposition that contradicts the speaker’s bias. The common ground may then be updated, but in

a way that is not anticipated by the speaker, especially when the speaker denies an unexpected

but actual event that s/he has failed to cognitively integrate.

The mirative nature of emotion-induced rhetorical questions has important theoretical

implications. As argued by Alcázar (2017: 37), mirative rhetorical questions express “antithesis

of the Common Ground”, which goes against standard treatments of rhetorical questions. In line

with Alcázar, I believe that the deictic essence of the rhetorical questions under study accounts

for their mirative meaning

26

. Evidence of this deictic component may be supplied by their

resistance to the embeddability test. Mirative meaning is lost in an embedded clause (see Rett

and Murray 2013, Celle et al. 2017):

(15’) Dolores asked Ed what kind of sick mind would operate like that.

This embedded sentence cannot express Dolores’s surprise, contrary to the rhetorical question in

(15). Even if this sentence is turned into an exclamation, it can only express the speaker’s

surprise, not Dolores’s:

(15’’) Dolores asked Ed what kind of sick mind would operate like that!

However, it should be stressed again that in English, mirativity is not marked as such

morphosyntactically

27

. Predictably, the form and structure of mirative rhetorical questions do not

differ from those of non-mirative rhetorical questions. Combining a semasiological approach

with an onomasiological perspective offers a means to detect a meaning that might otherwise go

26

I view mirativity as an epistemic stance adopted in reaction to an unexpected event. Mirativity consists

in the expression of surprise, not in the description or assertion of surprise (Celle & al. 2017). Along this

line of reasoning, expressions like ‘I am surprised, ‘he was surprised’ are not mirative utterances. These

are assertions of surprise (see Rett & Murray 2013: 455). They need not be anchored to the time of

utterance or to the first and second persons. Such expressions can be embedded without any change in the

surprise meaning.

27

Nonetheless, there is typological evidence in support of mirative rhetorical questions. In Basque, for

example, mirative rhetorical questions are marked by ote, a mirative conjunction (see Alcázar 2017). In

Ashéninka Perené, Mihas (2014: 213-216) also shows that the enclitic =ma~=taima that commonly encodes

inference can occur in content questions to express mirative meaning, both in direct and indirect speech

acts (including rhetorical questions).

unnoticed for lack of a dedicated morpheme. It also enables us to enrich our understanding of

mirativity in English. DeLancey (2001: 377-378) suggests that mirativity is a “covert semantic

category” in English mainly expressed intonationally

28

. I further argue that rhetorical questions,

i.e. questions used as indirect speech acts, may serve a mirative function. One might wonder why

there is such an affinity between mirativity and rhetorical questions. From a schema-theoretic

perspective, surprise induces cognitive processing that starts with the search for a cause and

ultimately ends with belief revision (see Meyer et al. 1997: 253; Miceli & Castelfranchi 2015:

52). This highly adaptive psychological pattern is ideally mapped on rhetorical questions, which

call upon the addresse for commitment update to validate belief revision. Note that mirativity

and rhetorical questions have non-commitment in common. The epistemic stance adopted by a

speaker in reaction to unexpected information is typically one of non-commitment, as shown by

Zeisler (2017) on the use of ḥdug in Ladakhi

29

. Zeisler stresses that “SPEAKER ATTITUDE (or

STANCE) primarily deals with the relation between the speaker and the content of the utterance

and between the speaker and the addressee”. Rhetorical questions are also primarily addressee-

oriented as they request the addressee’s commitment, the speaker putting forward an answer

without committing to the truth of the proposition.

This leads us to refine the epistemically-based typology of questions proposed in Littell

et al. (2010). Questions are not only based on the speaker’s knowledge and beliefs.

30

They also

contribute to dialogue in a dynamic way by requesting the addressee’s commitment. Therefore,

an epistemically-based typology of questions should accommodate the request for commitment

update that distinguishes rhetorical questions from assertions. In a rhetorical question, the

speaker believes that the addressee knows the answer because the answer is suggested by the

question itself, although speaker and addressee may differ in their beliefs and appraisals

31

. In the

28

Mirativity in English is often associated with an exclamation intonation (Rett & Murray 2013).

Questions used as indirect speech acts do have an exclamation intonation and can convey mirative

meaning. As explained in Celle et al. (forthc.), surprise in questions used as direct speech acts is generally

induced by a discourse entity rather than by new environmental information. Although such questions do

express surprise, they should not be considered mirative.

29

Ḥdug is an auxiliary used to encode visual perception and non-commitment. Zeisler (2017) argues that

ḥdug has parasitic mirative connotations.

30

In addition, speaker’s knowledge is grounded in dialogue and articulated to indexical cues, as shown by

Du Bois (2007: 157).

31

By contrast, in an ordinary question, the addressee is asked to commit to her own answer.

case of mirative rhetorical questions, the commitment update cannot be taken for granted as it

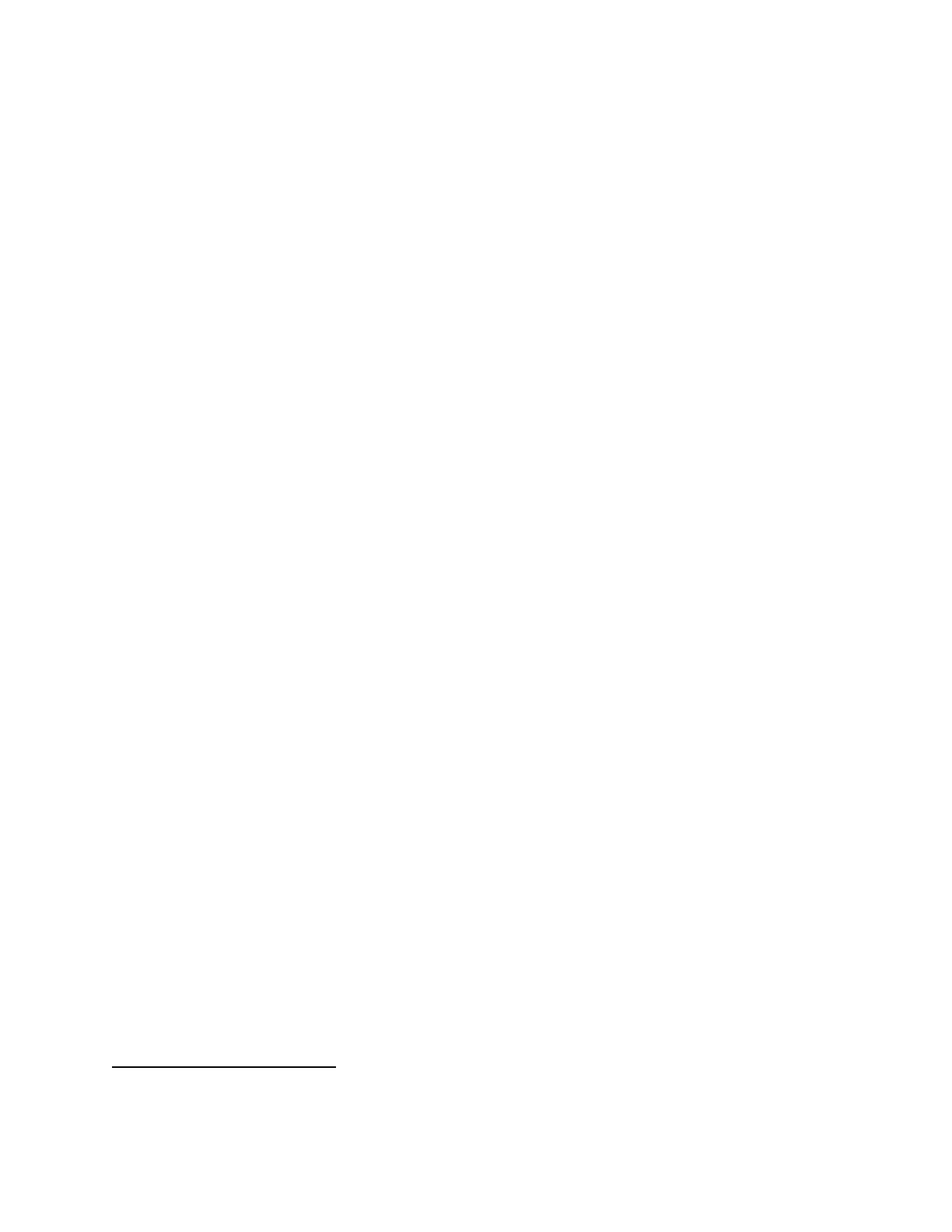

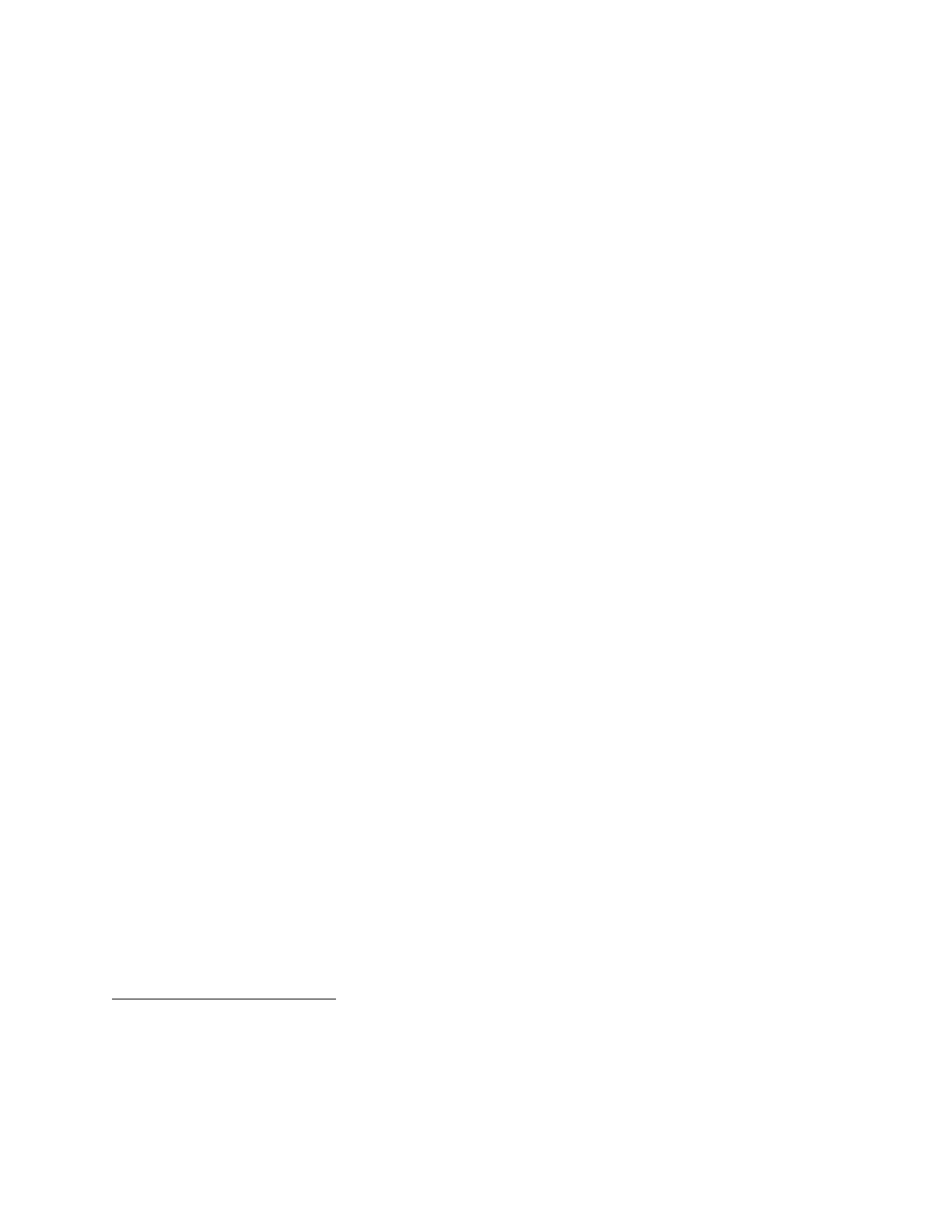

may be hindered by disagreement. These features are summed up below in Table 2.

[Insert Table 2 here]

Table 2. An epistemically- and dialogically-based typology of questions

Speaker knows

the answer

Speaker believes that the

addressee knows the answer

Speaker requests

addressee’s commitment

Ordinary

Questions

No

Yes

Yes

Rhetorical

Questions

Yes

Yes

Yes

Unresolvable

Questions

No

No

No

5. Conclusion

This chapter is part of a study of all question types used in reaction to surprising information. As

shown in Celle & al. (forthc.) 83% of the interrogatives found in our corpus of movie scripts are

questions used as direct speech acts. These questions request information that aims to increase

the speaker’s knowledge and are generally discourse-linked, that is, surprise is generated by

unexpected new linguistic information.

This chapter focused on the remaining 17% surprise-induced questions used as indirect

speech acts. It showed that in English, mirativity can be conveyed by two different types of

interrogatives used as indirect speech acts. Both surprise-induced rhetorical questions and

unresolvable questions take the form of interrogatives but do not request information. Rhetorical

questions are resolved questions, whereas unresolvable questions implicate that no resolution can

be reached. Their mirative meaning is conveyed by a discrepancy between what is observed and

what was expected. However, being generated by different types of surprising situations, these

questions exhibit mirative meaning at different stages of the cognitive assimilation of unexpected

new information.

Surprise-induced rhetorical questions are typically generated by counterfactual evidence.

By using such an indirect speech act, the speaker distances him/herself from the discrepant actual

state of affairs. Rhetorical content questions are found in reaction to some behavior for which the

addressee is held responsible. Their aim is to persuade the addressee to modify that behavior in

order to meet the speaker’s expectations. From a schema-theoretic perspective, rhetorical

questions may be viewed as the last stage of the surprise-induced appraisal process (see Meyer et

al. 1997: 253 cited above): they aim at a commitment update on the part of the addressee. Using

concepts borrowed from the schema-theoretic framework not only allows bridging the gap

between psychology and linguistics. It also sheds light on the shades of mirativity by correlating

them with different stages of the cognitive processing of new information induced by surprise.

Rhetorical questions appear to express mirativity at the semantic-pragmatic level as mirative

meaning is not associated with a specific morphosyntactic form in English. However, a

constellation of grammatical and lexical items (modal auxiliaries, deictics, degree words) is the

hallmark of mirativity.

Surprise-induced unresolvable questions tend to be triggered by directly perceived

evidence. The addressee’s agency is not involved – at least in my data – and a judgment of

incongruity is formed once the situation has been appraised either positively or negatively.

Whatever the answer – if any – it cannot account for the sense of incongruity attached to the

situation. This type of expressive speech act does not carry an epistemic goal. Rather, it carries

an instruction that no variable can be provided to instantiate the salient open proposition.

Mirativity projects from the initial stage of the cognitive assimilation of unexpectedness: “the

appraisal of a cognized event as exceeding some threshold value of schema-discrepancy (or

unexpectedness)” (Meyer et al. 1997: 253). At that stage, the surprise process produces a state of

ignorance and wonder. It is expressed by specific lexemes, that is, interjections and emotive

modifiers that provide the indirect speech act with an expressive force.

Pragmatically, rhetorical questions express a biased position and are generally said to

point to an obvious answer. The present chapter offers an alternative analysis that accounts for

the apparent paradox of rhetorical questions being used in reactions of surprise. Contra Rohde

(2006), I argue that informativity and update of the participants’ commitment sets should be

distinguished. In surprise-generated rhetorical questions, although no informative answer is

requested, a two-fold update is expected. First, rhetorical questions signal the speaker’s attempt

to cognitively assimilate new environmental information, the actual state of affairs being

counterexpectational. Second, they request a commitment update on the part of the addressee in a

questioning process triggered by the speaker’s and the addressee’s conflicting views. Rhetorical

questions show that surprise, in association with other emotions it contributes to generating (such

as anger), can be exploited within complex argumentative strategies, as evidenced in other

research works on the lexicon of surprise (see Tutin 2017; Celle et al. 2017). Emotion-induced

rhetorical questions serve an argumentative function whereby the addressee is asked to commit

to a proposition that the speaker does not commit to in a direct way. Rhetorical questions offer a

pragmatic means to attempt to reduce the belief discrepancy associated with the experience of

surprise. However, if the belief discrepancy cannot be reduced - in case of strong disagreement -

they take on a challenging function.

Unlike rhetorical questions, unresolvable questions are generated by evidence judged

incongruous. They are speaker-oriented, the speaker attempting to emotionally adapt to an

incongruous situation without expecting an answer or even a response of the addressee. In

English, interjections and emotive modifiers encode the mirative meaning of unresolvable

questions. Further investigations are needed to better assess their respective contributions to

mirativity. The claim made in this chapter is that in English, expressives can change the

illocutionary force of a sentence in the same way as evidentials in other languages. This can be

explained on the grounds that evidentials and expressives share common features. Emotive

modifiers and interjections are illocutionary modifiers triggered by direct evidence. They encode

the speaker’s emotional experience, while evidentials encode the speaker’s perceptual or

cognitive experience. In sum, both evidentials and expressives encode speaker perspective

32

.

Further investigations are needed to better assess the respective contributions of expressives and

evidentials to interrogatives.

This chapter offers a refinement of Littell et al.’s (2010) typology of questions by

including the commitment update parameter. It also proposes to distinguish between conjectural

questions and unresolvable questions. In conjectural questions, the speaker knows the answer

32

See San Roque et al. (2017). Potts (2007: 173) argues that expressives may be embedded and involve

“perspective dependence” rather than strictly speaker perspective.

and only seeks the addressee’s commitment to the truth of the proposition. In unresolvable

questions, emotive modifiers change the illocutionary force by implicating that neither speaker

nor addressee can provide an answer.

These findings also suggest that unresolvable questions are generated by outcome-related

surprise, while rhetorical questions are generated by person-related surprise

33

. I leave it to future

research to determine whether this distinction is reflected in the appraisal pattern and whether it

generates differences in linguistic responses. The complex relation between evidence-induced

mirative utterances and discourse-based topic-comment constructions is also an avenue for future

research.

References

Akatsuka, Noriko. 1985. Conditionals and the epistemic scale. Language 61(3): 625-639.

Alcázar, Asier. 2017. A syntactic analysis of rhetorical questions. In Proceedings of the 34th

West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, Aaron Kaplan, Abby Kaplan, Miranda K.

McCarvel & Edward J. Rubin (eds), 32-41. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings

Project.

Ameka, Felix. 1992. Interjections: the universal yet neglected part of speech. Journal of

Pragmatics 18(2) : 101-118.

Azzopardi, Sophie & Bres, Jacques. 2014. Futur, conditionnel, et effets de sens de conjecture et

de rejet en interrogation partielle. SHS Web of Conferences 8 : 3003-3013.

Beyssade, Claire, & Marandin, Jean-Marie. 2009. Commitment: une attitude dialogique. Langue

française 162: 89-107.

Bourova, Viara & Dendale, Patrick. 2013. Serait-ce un conditionnel de conjecture? Datation,

33

Van Dijk and Zeelenberg (2002) distinguish between outcome-related vs. person-related

disappointment. Ortony et al. (1988) make a similar distinction between event-based and agent-based

emotions. This distinction can be fruitfully applied to surprise and helps account for the connection

between surprise and anger observed in the case of rhetorical questions, anger being a person-related

emotion.

évolution et mise en relation des deux conditionnels à valeur évidentielle. Cahiers

Chronos 26 : 183-200.

Caponigro, Ivano & Sprouse, Jon. 2007. Rhetorical questions as questions. In Proceedings of

Sinn und Bedeutung 11, E. Puig-Waldmüller (ed.), 121-133. Barcelona: Universitat

Pompeu Fabra.

Carroll, James M. & Russell, James A. 1997. Facial expressions in Hollywood’s portrayal of

emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72 : 164-176.

Celle, Agnès. 2007. Analyse unifiée du conditionnel de non prise en charge en français et

comparaison avec l’anglais. Cahiers Chronos 19, Etudes sémantiques et pragmatiques

sur le temps, l’aspect et la modalité : 43-61.

Celle, Agnès. 2009. Question, mise en question: la traduction de l’interrogation dans le discours

théorique. Revue Française de Linguistique Appliquée XIV/1: 39-52.

Celle, Agnès. in press. Epistemic evaluation in factual contexts in English. In Epistemic Modality

and Evidentiality in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective, Zlatka Guentchéva (ed.). Berlin:

Mouton de Gruyter.

Celle, Agnès & Lansari, Laure. 2014. Uncertainty as a result of unexpectedness. Language and

Dialogue 4(1) 7-23.

Celle, Agnès & Lansari, Laure. 2015. On the mirative meaning of aller + infinitive compared

with its equivalents in English. Cahiers Chronos 27, Taming the TAME systems: 289-

305.

Celle, Agnès, & Lansari, Laure. 2016. L’inattendu et le questionnement dans l’interaction

verbale en anglais: les questions en why-would et leurs réponses. In Représentations du

sens linguistique: les interfaces de la complexité, Olga Galatanu, Ana-Maria Cozma &

Abdelhadi Bellachhab (eds.), 235-248. Bruxelles: Peter Lang.

Celle, Agnès, Jugnet, Anne, Lansari, Laure & L’Hôte, Emilie. 2017. Expressing and describing

surprise. In Expressing and Describing Surprise, Agnès Celle & Laure Lansari (eds),

215-244. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Celle, Agnès, Jugnet, Anne, Lansari, Laure & Peterson, Tyler (forthc.) Interrogatives in surprise

contexts in English. In Surprise at the Intersection of Phenomenology and Linguistics,

Natalie Depraz & Agnès Celle (eds.). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Darwin, Charles. 1965. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

DeLancey, Scott. 2001. The mirative and evidentiality. Journal of Pragmatics 33: 369-382.

Dendale, Patrick. 2010. Il serait à Paris en ce moment. Serait-il à Paris? A propos de deux

emplois épistémiques du conditionnel: grammaire, syntaxe, sémantique. In Liens

linguistiques. Études sur la combinatoire et la hiérarchie des composants, Castro

Camino Alvarez, Flor Marίa Bango de la Campa & Marίa Luisa Donaire (eds), 291-317.

Bern: Peter Lang.

Den Dikken, Marcel & Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2002. From hell to polarity: “aggressively non-

D-linked” wh-phrases as polarity items. Linguistic Inquiry 33(1): 31-61.

Desmets, Marianne & Gautier, Antoine. 2009. “Comment n’y ai-je pas songé plus tôt ?”

Questions rhétoriques en comment. Travaux de linguistique 58 : 107-125.

Diller, Anne-Marie. 1977. Le conditionnel, marqueur de dérivation illocutoire. Semantikos 2: 1-

17.

Du Bois, John. 2007. The stance triangle. In Stancetaking in Discourse, Robert Englebretson

(ed.), 139-182. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Fillmore, Charles. 1985. Syntactic intrusions and the notion of grammatical construction.

Proceeding of the Eleventh Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: 73-86.

Ginzburg, Jonathan. 2012. The Interactive Stance: Meaning for conversation. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Guentchéva, Zlatka. 2017. An enunciative account of admirativity in Bulgarian. Review of

Cognitive Linguistics, The linguistic expression of mirativity, Special Issue 15(2): 539-

574.

Gunlogson, Christine A. 2001. True to Form. Rising and Falling Declarative as Questions in

English. PhD Dissertation, University of California, Santa.

Huddleston, Rodney & Pullum, Geoffrey. 2002. The Cambridge Grammar of the English

Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haillet, Pierre-Patrick. 2001. A propos de l’interrogation totale directe au conditionnel. In Le

conditionnel en français, Recherches linguistiques 25, Université de Metz, Patrick Dendale &

Liliane Tasmowski (eds.), 295-330.

Hoeksema, Jack & Napoli, Donna Jo. 2008. Just for the hell of it: a comparison of two taboo-

term constructions. Journal of Linguistics 44: 347-378.

Kay, Paul, & Fillmore, Charles. 1999. Constructions and linguistic generalizations: the what’s X

doing Y? construction. Language 75(1): 1-33.

Korotkova, Natalia. 2016. Heterogeneity and Uniformity in the Evidential Domain. PhD

Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles.

Littell, Patrick, Matthewson, Lisa & Peterson, Tyler. 2010. On the semantics of conjectural

questions. In Evidence from Evidentials, Tyler Peterson & Uli Sauerland (eds), 89-104.

University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics (UBCWPL).

Meyer, Wulf Uwe, Reisenzein, Rainer & Schützwohl, Achim. 1997. Toward a process analysis

of emotions: the Case of Surprise. Motivation and Emotion 21(3): 251-274.

Miceli, Maria & Castelfranchi, Cristiano. 2015. Expectancy and Emotion. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Michaelis, Laura & Feng, Hanbing. 2015. What is this, sarcastic syntax? Constructions and

Frames 7(2): 148-180.

Michaelis, Laura & Knud, Lambrecht. 1996. The exclamative sentence type in English. In

Conceptual Structure, Discourse and Structure, Adele Goldberg (ed.), 375-389. Stanford:

CSLI.

Mihas, Elena. 2014. Expression of information source meanings in Ashéninka Perené (Arawak).

In The Grammar of Knowledge, A Cross-Linguistic Typology, Alexandra Aikhenvald,

Robert Dixon & Malcolm Ward (eds), 209-226 Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ortony, Andrew, Clore, Gerald L. & Collins, Allan. 1988. The Cognitive Structure of Emotions.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pesetsky, David. 1987. Wh-in-Situ: movement and unselective binding. In The Representation of

(in)Definiteness, Eric Reuland & Alice ter Meulen (eds), 98-129. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

Peterson, Tyler. 2017. Grammatical evidentiality and the unprepared mind. In Expressing and

Describing Surprise, Celle Agnès & Laure Lansari (eds), 51-89. Amsterdam: John

Benjamins.

Pinker, Steven. 2007. The Stuff of Thought: Language as a window into human nature. New

York: Penguin.

Potts, Christopher. 2005. The Logic of Conventional Implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Potts, Christopher. 2007. The expressive dimension. Theoretical Linguistics 33(2): 165-198.

Reese, Brian. 2007. Bias in Questions. PhD Dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin.

Reisenzein, Rainer. 2000. Exploring the strength of association between the components of

emotion syndromes: the case of surprise. Cognition and Emotion 14(1): 1-38.

Rett, Jessica & Murray, Sarah. 2013. A semantic account of mirative evidentials. In Proceedings

of SALT 23: 453-472.

Rocci, Andrea. 2007. Epistemic modality and questions in dialogue. The case of Italian

interrogative constructions in the subjunctive mood. In Tense, Mood and Aspect:

Theoretical and descriptive issues, Louis de Saussure, Jacques Moeschler & Genoveva

Puskas (eds), 129-153. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Rohde, Hannah. 2006. Rhetorical questions as redundant interrogatives. San Diego Linguistics

Papers, Vol. 2, University of California, San Diego: 134-168.

San Roque, Lila, Floyd, Simeon & Norcliffe, Elisabeth. 2017. Evidentiality and interrogativity.

Lingua 186-187: 120-143.

Scherer, Klaus, Clark-Polner, Elizabeth, Mortillaro, Marcello. 2011. In the eye of the beholder?

Universality and cultural specificity in the expression and perception of emotion.

International Journal of Psychology 46(6): 401-435.

Siemund, Peter. 2017. Interrogative clauses in English and the social economics of questions.

Journal of Pragmatics 199: 15-32.

Stein, Nancy L. & Hernandez, Marc W. 2007. Assessing understanding and appraisals during

emotional experience. In Handbook of Emotion Elicitation and Assessment, James A.

Coan & John J. B. Allen (eds), 298-317. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stivers, Tanya. 2010. An overview of the question-response system in American English

conversation. Journal of Pragmatics 42(10): 2620-2626.

Tutin, Agnès. 2017. Surprise routines in scientific writing: a study of French social science

articles. In Expressing and Describing Surprise, Agnès Celle & Laure Lansari (eds), 153-

172. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Van Dijk, Wilco W. & Zeelenberg, Marcel. 2002. What do we talk about when we talk about

disappointment? Distinguishing outcome-related disappointment from person-related

disappointment. Cognition and Emotion 16(6): 787-807.

Vingerhoets, Ad, Bylsma, Lauren & De Vlam, Cornelis. 2013. Swearing: a biopsychosocial

perspective. Psychological Topics 22 (2013), 2, 287-304.

Zaefferer, Dietmar. 2001. Deconstructing a classical classification: a typological look at Searle’s

concept of illocution type. Revue internationale de philosophie 2001/2 (n° 216), 209-225.

Zeisler, Bettina. 2017. Don’t believe in a paradigm that you haven’t manipulated yourself ! -

Evidentiality, speaker attitude, and admirativity in Ladakhi. Review of Cognitive

Linguistics, Special Issue 15(2): 515-538.